The more neurologists find out about the brain, the more awestruck we can become at the complexity of what goes on inside our heads. How does neuroscience fit in with spiritual experience? Is a neurologist likely to struggle with the idea of God?

Alasdair Coles has had a unique career path. An academic neurologist, conducting research into multiple sclerosis in one of Europe’s finest teaching hospitals, he has recently been ordained in the Anglican church. He is now a hospital chaplain, in addition to his clinical and teaching roles. Alasdair’s experience as a Christian in neurology has been a very positive one, and as he begins to minister in both the church and the workplace he is discovering some valuable connections between faith and science.

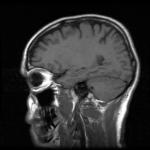

Ever since I stopped wanting to fly fighter planes, at around the age of fifteen, I’ve wanted to be a neurologist. I specifically wanted to work with people who have diseases of the brain. The thing that has always interested me is finding out how much the physical structure of the brain can explain our behaviour.

In a church environment my interest in the brain and its behaviour is obviously out of the ordinary compared to a lot of ministers. I often talk about my amazement at the way the brain is put together, and in a pastoral context I’m much more open to the body influencing our state of mind. One of the attractions of the Christian faith for me is that it’s ‘embodied’. The Bible recognises that we are bodies as well as rational moral beings.

We are dependent on our brains to be conscious and aware, to reflect on ourselves, to have moral reasoning and to have desires and hopes. We have a brain that has the capacity for religious experience. We may or may not find ourselves in an environment (social or biological) which allows this religious expression to thrive. Each person then has the ability to decide for themselves whether or not to allow this spiritual awareness to flourish and at that point God can intervene. When you deal with someone who’s struggling, then looking at their physical state is absolutely as important as their spiritual and mental state. I think that is a very important first start for tackling problems: staying fit, getting rest, not drinking too much, not abusing drugs. You’ve got to make the best of that person’s brain and body and then they’re giving themselves the best chance to be spiritually aware.

I believe it is a mistake to say the ‘soul’ is an independent entity that tells the brain what to think. It is also a mistake to say that the soul is nothing but the brain and that everything a person does is explained by the neurons (brain cells) themselves. It’s obvious to me that that isn’t true or at least not true in any helpful ordinary way. Consider: how do we best explain personality? How do we explain human behaviour? You could explain a painting on the basis of the chemicals that make up the oil paints. That would be a perfectly true explanation but most people would find that thoroughly unsatisfactory as an explanation of a painting. They would want to say, ‘There’s more to it than that, someone made this, it has a significance that is dependent on the oils but ultimately it has nothing to do with them.’ Human thoughts and behaviour are dependent upon, but in some way separate from, the material of the brain. You can either believe that God made us or that evolution made us or both, but we are made for a purpose.

My hospital community lacks prominent Christian voices. It’s interesting that the hospital chaplains will tell you that the group of people they have most difficulty approaching are the ‘alpha male’ senior doctors. We are a very distinct tribe and closed off. Academic neurologists are a very unspiritual group of people. It is very unusual for a neurologist to be a credited minister, and religion and spirituality are not welcomed as topics of conversation. Although I’ve never encountered any hostility, I’ve certainly met with curiosity but rarely positive support. The most common reaction is lack of interest or a feeling that this is slightly eccentric. However, one person has made a great deal of difference to my faith in the workplace. I am very fortunate to have a friend and colleague who is a strong Christian. We agreed a few years ago to meet together to read the Bible and pray once a week. Then we decided to open up to all Christians in our workplace. Now up to fifteen people meet once a week to study a Bible passage and pray. We pray for the hospital, for the people working here and for the patients. Leaving aside what that means for the institution and whether there should be more of it, for me it’s powerful that I bring my faith to work and that people around me know that I’m a Christian so I can be held accountable for that.

The ‘added value’ of having a faith comes in lots of different ways. One of the things it has done is to make me ask if there is a neurological basis for religious experience. How do we fit faith into the working brain and at what level? These issues have never been a problem for my own beliefs. I think if anything my faith has encouraged me to keep asking questions, because at heart I think I’m just a child who’s enthralled with things. I have come to understand that feeling of pleasure and joy as a gift from God and an encouragement for me to carry on.

My interest in the structure of the brain and how it affects behaviour is stronger now than it ever has been. I would say that my faith encourages me to look into ‘the book of life’ and read the work of God. Neurology is what I like and what I’m good at, and I think God shares that pleasure with me. It’s never been a problem for me and I’m always surprised when I meet people who talk about conflict between the two.

This post was first published on everythingconference.org, and is an extract from Test of FAITH: Spiritual Journeys with Scientists, Ruth Bancewicz (ed.), (Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2009/Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock, 2010). Used with permission of the publishers and the Everything Conference.