This post is the last in a series of three from an interview with Professor Jeff Hardin of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I love what he says here about aesthetics, transcendence, and the feeling of worship that a scientist can feel when they’re in the lab. (Part 1 here, part 2 here.)

To me, there’s something wrong with you as a Christian and a scientist if you don’t have a personal investment in the material that you’re trying to convey. I think my colleagues also share my sense of wonder about the world. Why exactly is that? Why do we have a sense of wonder? I could talk about Rudolph Otto’s ‘sense of the numinous’. But can we get to something a little bit more concrete than that? I think it’s, as Tom Wright says, an ‘echo of a voice’. Creation itself is calling out to us, saying something about its creator. That’s what motivates me as a scientist.

Science for a Christian, in some very real sense, is an exercise in art appreciation, and art historians must take the works of art on their own terms and try to understand them. The theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar has written a good deal about aesthetics, and how it feeds into epistemology (how we know what we know), and even to metaphysics. I’m trying to explore that in my own thinking and reading. For me, being a Christian means that I need to take the contingent world as it is and understand it as well as I can, in the same way that someone who’s studying a work of art must take it as it is and try to understand it for its own sake, as well as he or she can.

I think the tendency at times in the States is to be suspicious of people of faith when they come to doing science. But I would argue that Christians ought to be better scientists because they have to take the world on its own terms. There’s the analogy of the ‘two books’ – which comes from Psalm 19 – the book of God’s works in the world and the book of God’s word, which for Christians is the Bible. We need to take each of those books incredibly seriously. The regularity of heavenly bodies is the subject of discussion in Psalm 19, but there are other Psalms that talk about biological process, including predator-prey relationships and everything else. It’s clear in these pieces of poetry that understanding those biological processes as well as you can is actually an exercise in giving glory to the one who stands behind them. To me that’s part and parcel of being a scientist.

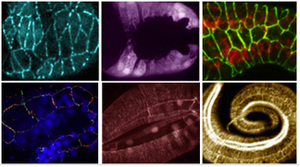

Theoretical chemist Fritz Schaefer was quoted a number of years ago in an American news magazine as saying that when he discovers something for the first time he has a moment where he thinks, ‘Aha, that’s how God did it!’ That moment is very like when you go on a hike and there’s a special spot at the end with a beautiful view that not many people know about. The natural response is to want to share that with somebody. I think the same is true in science, and as a Christian I want to share that discovery with God himself. It becomes an act of worship for me.