“Look at the yeast fields, for they are already white for harvest!”, wrote Dr Maria Eugenia Inda, one of the winners of the American Society for Microbiology ‘Agar Art’ contest. I’m not sure she meant anything more than to pick up a quote remembered from the Bible and subvert it for a scientific message – the “Harvest Season” of yeast knowledge – but it made me think.

Maria is a researcher from Argentina who went to a summer course at the Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory near New York. One of the organisms they studied was a species of yeast called Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which has been used by bakers, beer makers and vintners for thousands of years.

Yeast is a fungus that shares many of the basic processes which happen in other organisms, including ourselves, so it’s also very useful for medical research. It was the first organism more complex than a bacterium to have its entire genome (all its DNA) decoded. I remember the release of these data when I was at university in the 1990’s. It was a huge achievement at the time, and opened up all sorts of new avenues for research.

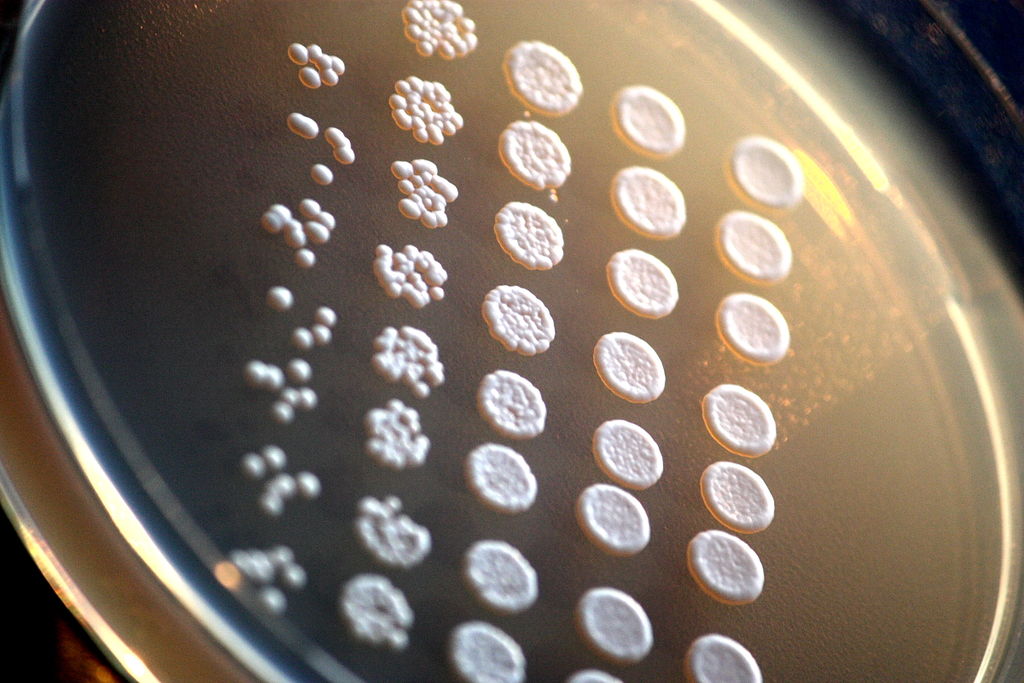

Drop-inoculation of laboratory baker´s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) mutants on agar plate. By Rainis Venta (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

The altered plasmids – perhaps containing a gene you want to know about or a factor that will affect the yeast’s biology in some way – can be reintroduced to live yeast cells, to study their effect. A quick search of the latest biology papers shows me that S. cerevisiae has recently been used to study the replication of DNA, toxicity of metals, the production of industrial waxes, and ways to control a fungus that attacks citrus fruit.

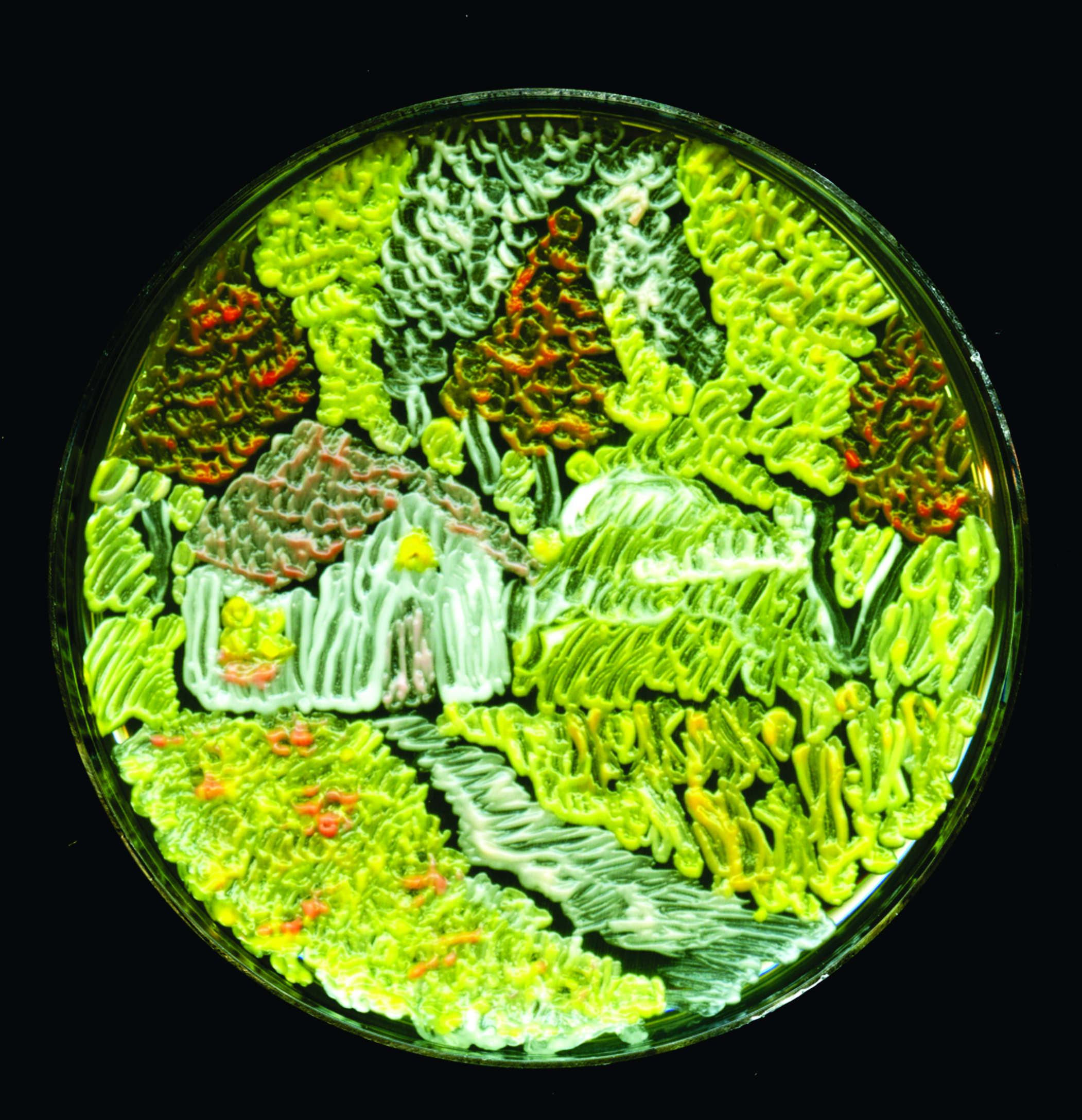

Maria’s art competition entry happened because she found herself studying some types of yeast that had been genetically engineered to produce different amounts of the natural pigment beta-carotene. With some spare time and a ready made palette of yeast colours to work with, it was easy for Maria to paint a picture on agar – the solid jelly that’s often used for growing yeast or bacteria in petri dishes. She drew a farmhouse surrounded by wheat fields, which for her was symbolic of the potential for yeast to contribute to our scientific knowledge. After some time quietly growing in an incubator, the picture was complete. In between the hard graft of setting up experiments, some art was produced.

Harvest Season © American Society for Microbiology and Maria Eugenia Inda, CSHL

I was immediately grabbed by Maria’s use of the verse from John’s gospel, because this is how I see science. For many Christians in the lab, research is a way of using our skills to serve God. The context of the verse is about people who are seeking God, but the wider context is of Jesus establishing a new way of living. Scientists are part of that way, contributing to society, helping to heal the sick, feed the hungry, and providing new ways to worship God by showing how amazing his creation is. So when a new door opens – as happened when the yeast genome was sequenced – the fields are white for a harvest of new discoveries.

The ASM Agar Art Challenge: http://www.asm.org/index.php/asm-newsroom2/press-releases/94018-the-american-society-for-microbiology-announces-winners-of-the-agar-art-challenge

© Ruth Bancewicz, Nigel Bovey

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University, based at the MRC Human Genetics Unit. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth then moved to The Faraday Institute to develop the Test of FAITH resources, the first of which were launched in 2009. Ruth is a trustee of Christians in Science and on the advisory council of BioLogos.