A New Voyage by Brooks Bailey – Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Water is a strange thing. The unique structure of its molecules allow it take on three different forms: a liquid that is easily absorbed into porous substances (i.e. it’s wet!), ice that floats, and a gas. In the book Water and Life: The Unique Properties of H2O, the biophysicist Felix Franks has contributed a chapter explaining some of these properties, and how they may have played a part in the origin of life.

The chemistry of life has adapted to water and become very dependent on it, so that even ‘heavy water’[i] is toxic in large doses[ii]. But where did water come from in the first place? No one is completely sure, but HO (as opposed to H2) seems to be the most common chemical in space after hydrogen. Water is present on the interstellar dust particles that come together to form comets. There is solid water in cold stars and meteorites, and signs of some sort of water have even been detected in the sun.

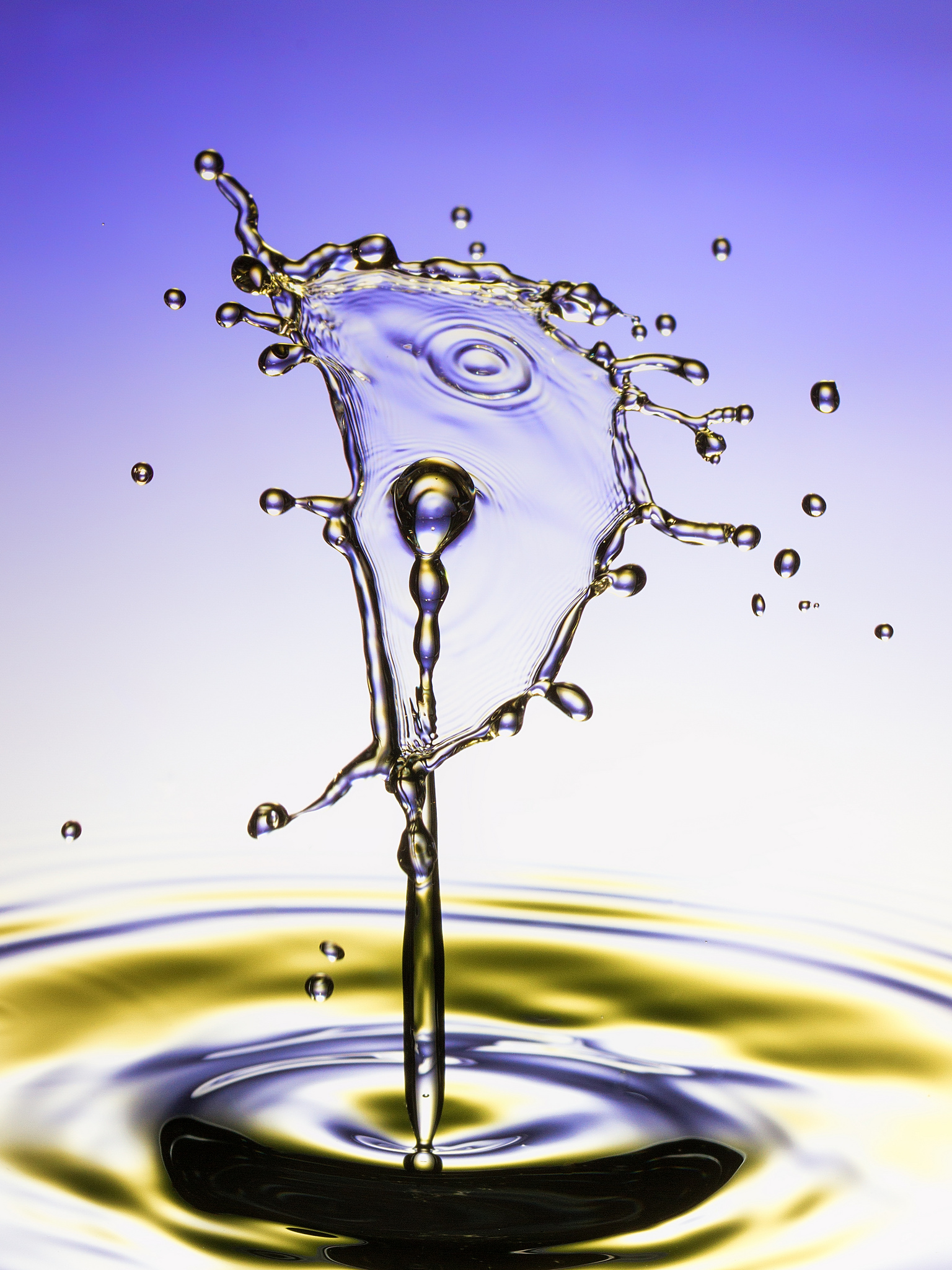

Purple Yellow Collision by Joe Dyer – Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

The most plausible theory for the presence of a large amount of water on earth is that it arrived[iii] when the temperature of the planet was above 374oC, which is a critical temperature for water. As the amount of water built up, it would have been at such a high pressure that at this temperature it was neither liquid nor gas. As the earth cooled, the water suddenly condensed. Some of the water would have evaporated away and formed the atmosphere, and the rest became the oceans.

The first cells may well have formed in hot deep-sea trenches where no oxygen was present. They used the energy-containing hydrogen atoms in water to power their biochemical reactions, releasing oxygen molecules (O2) in the process. Molecular oxygen disrupts biochemical reactions, but eventually organisms (including ourselves) developed that could use oxygen, releasing carbon dioxide in the process.

It is ironic that we classify anaerobic (not using oxygen) life forms as ‘extremophiles’. It would make sense to use this word for the more recent life forms that tolerate oxygen, or even depend on it. Many organisms have successfully made the transition to land, although their cells contain an average of 80% water. Land-dwelling organisms are full of mechanisms to maintain the correct water balance, and mammalian babies develop in a watery environment with a similar composition to the sea.

Surgent by fs999 – Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Today, there are 1.34 billion (109) square kilometres of water on earth, 97% of which is in the oceans. Most of the remainder is frozen in the Antarctic icecap, so around 0.003% of the total is available as liquid freshwater at any one time. 75% of this freshwater water is used as irrigation, and 3% is available in streams and lakes. The rest of the freshwater is in the ground, and even desert sand contains an estimated 15% of water. Surface water is recycled and purified about 37 times each year through the water cycle.

Waterfall-Skye by Luis Ascenso – Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Of course, research has been continuing since Franks wrote his article, and water has been found on other moons or planets. The fact remains that our planet is a fabulous place to live, and worth preserving. The water cycle is incredibly important for life on earth, and is currently being affected by climate change. Here’s hoping that last year’s United Nations Conference on Climate Change leads to lasting solutions to this problem.

[i] Where most of the hydrogen atoms contain a proton and a neutron in their nucleus, compared to normal where they just contain a proton.

[ii] It’s used in small quantities for metabolic studies. To kill a person they would have to drink it for several days, until it had replaced about 50% of their body fluids.

[iii] Probably via the impact of multiple comets.

Photo credit: Nigel Bovey

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University, based at the MRC Human Genetics Unit. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth then moved to The Faraday Institute to develop the Test of FAITH resources, the first of which were launched in 2009. Ruth is a trustee of Christians in Science and on the advisory council of BioLogos.