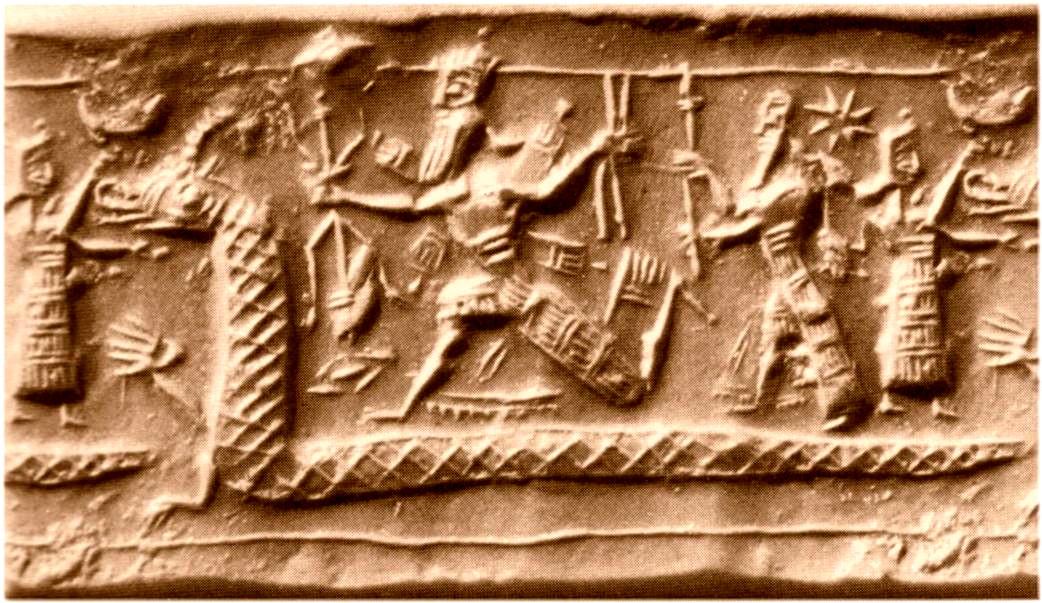

Babylonian cylinder seal. Ben Pirard at nl.wikipedia CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], Wikimedia Commons

“Once upon a time, there was a demiurge called Tiamat. Tiamat was the ocean, chaotic and powerful. Tiamat’s husband, freshwater, was troubled by their sons – the gods – who had come together and made great noise, and wanted to kill them. Tiamat disagreed and warned them. But when Tiamat’s husband was then killed by the gods she wanted revenge, so she made eleven monsters to hunt them down. In the end, the young champion Marduk challenged Tiamat to a battle and killed her. Marduk cut Tiamat in two, using one half of her body to create the heavens, and the other the earth.”

When the people of Israel were exiled in Babylon, if any of their youngsters ever got to receive an education they might have been taught the Babylonian creation poem Enuma Elish. The highly abbreviated version I have given here is just a flavour of this extremely – to my ears – somewhat violent epic. I wonder what the parents might have thought about their children being exposed to stories like this?

In her book The Luminous Web, Barbara Brown Taylor, an American author, lecturer and former priest, tells how she visited a parishioner who was sounding off about how terrible it was that young people these days are taught evolution at school: “Can you imagine teaching children that they come from monkeys instead of from God?” Barbara tried to explain that “evolution seemed like a kind of miracle” – the means by which God might have created us “from the dust” – but her words were falling on deaf ears.

The next day, Barbara explained to some theology students how the Hebrews in Babylon might have found themselves in a similar position, and felt the need to record their own creation story – the truth that had been revealed to them about the one true, loving, God who created the heavens and the earth. I found this perspective very helpful in understanding our situation today. The question for people like me is, how can I encourage Christians who want to keep their distinctiveness as people who believe in the Bible’s creation narrative, when we hear what might seem to be alternative creation stories in science?

I don’t know about the Enuma Elish, but the story at the beginning of Genesis reflects the most up to date ‘science’ of the day. Science as we know it wasn’t done till much later, but people in the Ancient Near East had ideas about how the world was ordered, with a solid dome in the sky, with windows in it for letting out rain. The sun moved around the earth, and the stars were about the same distance away as the clouds. The whole of the Old Testament reflects this worldview.

The evangelical Biblical scholar John Walton believes that“God did not seek to give [the Biblical writers] different information; he was not revealing “true” science.” He wrore “Those of us who take the Bible seriously believe that the Bible was given by God for all of us. Yet…it is not in our language and it is not communicated with our culture in mind”, so “the science of the Bible is not what has to be defended when we are seeking to understand its truth claims.”

Any thorough investigation of what the Bible means can turn up details like this. To give a less controversial example, I believe the part in one of Paul’s letters about women covering their heads during times of worship was a response to a particular cultural sensitivity of the day – so I don’t personally wear a hat to church. The primary issue – that we must worship God – is not at stake, but a few people might disagree with me on the secondary hat-wearing issue. In the same way, all Christians believe that God created the universe (the primary issue). On a secondary level, although no one (as far as I know) still thinks the rain comes through windows in a dome over the earth, some choose to reject the modern evolutionary view of the world.

So, back to Taylor’s story of the woman and the young people who were being taught mainstream science in school. The ancient Hebrews were ok with the prevailing view of the earth’s structure – that wasn’t the important issue – but they did believe the primary theological truth about who God is and what he has done. I think Christians can help the young people in our lives see what’s distinctive about our faith, not by rejecting mainstream science – because this is not the primary theological message of the Genesis text – but by getting to grips with the true theological meaning of the Biblical creation story. What does it say about what God has done, and what he made us to do? In this way, we can release young people to revel in both science and the Bible.

Further Reading

The Enuma Elish

John Walton on interpreting Genesis

Barbara Brown Taylor, The Luminous Web (Canterbury Press, 2000, 2017) – not my usual bedtime reading. There are other texts I would recommend for a first read on science and theology, but contains some interesting insights.

© Faraday Institute

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth arrived at The Faraday Institute in 2006, and is currently a trustee of Christians in Science.