Nanostar, scienceimage.csiro.au, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

Physicists working at the atomic or molecular scale are revolutionising industry with their ultra-small chips and mini-machines, but in a sense nanotechnology is nothing new. Nature got there first, and we are only just beginning to catch up – both in what we can manage technically, and in our understanding of the nano-forces that shape molecules and cells. These are just some of the topics that Russell Cowburn, Professor of Experimental Physics at Cambridge University, addressed when he spoke on The God of Small Things: Nanotechnology, Creation and God at the Faraday Institute earlier this month.

Cowburn studies thin film magnetism, and his research has resulted in the development of low energy computer chips, ultrahigh density 3-dimensional data storage, and healthcare devices. Cowburn is also a Christian, and he speaks regularly about the importance and ethics of nanotechnology, as well as the relationship between science and religion.

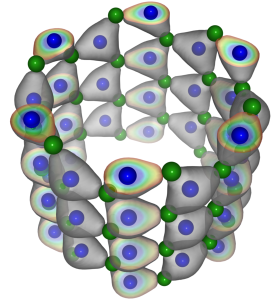

Boron nitride nanotube, Isaac Tamblyn, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

The nano-scale ranges from single atoms to whole virus particles, with carbon nanotubes and quantum dots in-between. These tiny packages can be visualised using atomic force-microscopy (AFM), where the movements of a tiny needle are detected by a laser beam. Scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) does essentially the same thing using an electrical charge. If AFM and STM are the eyes of a nanotechnologist, electron-beam lithography – what Cowburn described as an upside-down electron microscope – provides the hands in the form of a controlled beam of electrons.

The useful thing about nanotech is that materials take on very different properties when you work at very small scales. So it is possible to make tiny transistors that do the same job as the great chunks of metal used in the 1950’s; carbon can be shaped into thin films of graphene that are stronger than steel; and extremely thin films of metals make efficient photovoltaic cells.

One of the challenges of this work is in understanding the toxicity of nanomaterials when they are loose in the environment, or our bodies. Sun cream, food additives, clothing and health products can all contain nanoparticles, and thankfully there is a good amount of work being done to guard against any potentially negative impacts of these on our health and the environment.

Having come to faith at the age of eighteen, Russell has not experienced much of the apparent tension between science and faith. He has been a Christian and a scientist for roughly equal lengths of time, and has found them to be complementary. His faith informs the way he works, and he is convinced that we should be developing good new technologies – fulfilling our mandate to steward the earth. He also believes that we need to keep these new materials as safe as possible, and has been involved in encouraging PhD students to consider the ethical issues of their work.

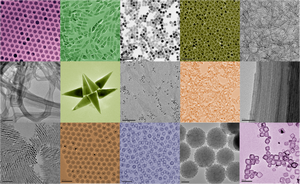

Nanoparticles, Taeghwan Hyeon. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

And what about the living world? How did nature get there first? It turns out that nano structures are basic to every form of life. The iridescent wings of certain butterflies have their colour because of nano structures rather than pigments. More importantly, every cell in your body is powered by a nano ‘machine’ called ATP synthase that creates chemical energy. One exciting question that scientists are beginning to ask is whether the origin of life involved the types of self-assembly behaviour that physicists are observing in the structures they study in the lab.

So the art and science of nanotechnology already affect every aspect of our lives and are on track to form the basis of the next industrial revolution, as well as improving our understanding of living things. For Cowburn, his work is a way of giving glory to God by revealing even more about the world God created. ‘I am fearfully and wonderfully made’ says Psalm 139, and we now know that God’s works are more wonderful than we had previously thought.

The field of nanotechnology, which brought people together from a wide range of scientific backgrounds to share techniques and insights, is bound to disperse as nano-scale technology becomes commonplace. For now, I am interested to see where this technology goes, how we can keep it safe, and how it can help us to live more sustainable lives.