Pixabay – CC0 Public Domain

One of our strongest intuitions is that we are in control of our own beliefs and actions. For the philosopher and biologist David Lahti, this freedom is real but imperfect. Rounding off our series on the Faraday summer course, this is the first of two posts on Lahti’s work on different aspects of being human.

In his lecture on Evolution and Moral Freedom, Lahti said that in his opinion there are no scientific data that threaten the idea of our freedom to choose. There may be all sorts of factors that influence our feelings, but we do seem to be in control of our behaviours and what we think about them. Our freedom to choose is indeed an integral part of being human. Most of us won’t have been waiting for an academic opinion on a point that probably seems so obvious to us. On the other hand, it is interesting to hear that science is not just on the same side as our common sense, but it also has some things to add to the discussion of how our free will operates.

Drawing on insights from behavioural ecology, Lahti explained a few elements of the discussion so far. First, we are partly shaped by our genes, but we are also guided by the perceptions and ideas we learned during our lifetimes. So our learning is biased by our evolutionary history, but there is a plasticity in our learning that allows us to modify our behaviour. From this complex interaction of influences and abilities, comes morality.

Pixabay – CC0 Public Domain

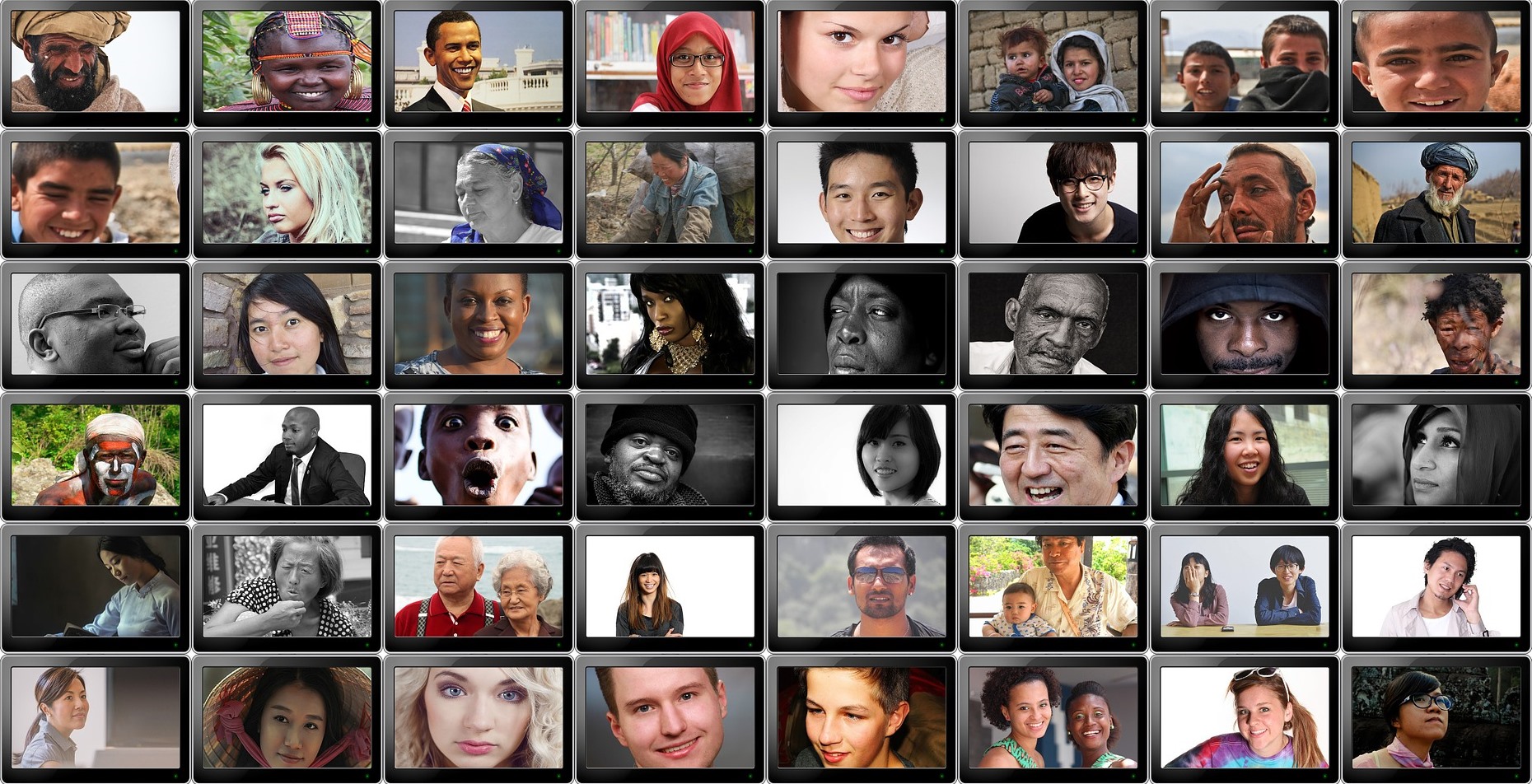

Secondly, the precursors of our moral views probably came to us by degrees, and from many different sources. Some moral behaviours are very old and have deep genetic roots, for example a mother’s love for her child. At the other end of the scale are more recent beliefs, like the idea that all people are of equal value, which draw on those roots but are modified by other traits and cultural influences.

Pixabay – CC0 Public Domain

Next, the crucible of human evolution has been the battle between competition and cooperation. As our own species became more dominant in the world, we eventually became our own worst enemy – competing for resources with our own kind. Self-serving behaviour is probably the oldest trait, as people competed for social status and mates within a group. Later on came competition between groups, driving cooperation between members of the same tribe or clan. Both of these mentalities can lead to behaviours we would view as morally good or morally bad – there is nothing about either that can help us to derive a moral code from them.

Finally, we are influenced by our own physical makeup as well as our surroundings, but those influences may have been a driver for developing morality in the first place. If temptations didn’t exist, why did we develop a mechanism for dealing with them? There are certain situations that force us to think hard, decide what we value most, and make moral decisions.

So what does all this mean? The oldest driver for morality was probably weighing up personal goals with the overall interests of the group. Do I eat the food or share it with my family? Other factors can then influence those choices. Groups tend to work better together during a crisis. I might also wonder, how can I gain a reputation as a good person? How can I keep on the right side of a difficult leader or help a rather shaky group stay together? If I am part of two groups, where do I place my loyalty? If a threat comes along, is it better to stick with my morals or let them change?

The most interesting factor for Lahti is when a behaviour used to be useful, but is now harmful. For example, children are more likely to survive in the wilderness if they enjoy sweet fruit, but if they eat too many sugary sweets their teeth will rot. Or the idea that mating with many others will spread our genes around more, but monogamy seems to be the best basis for bringing up children. Moral codes can help us adapt and flourish in new situations, from diet to marital relationships.

Parable of the Good Samaritan by Giacomo Conti (Accascina) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

© Ruth Bancewicz, Nigel Bovey

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth arrived at The Faraday Institute in 2006, and is currently a trustee of Christians in Science.