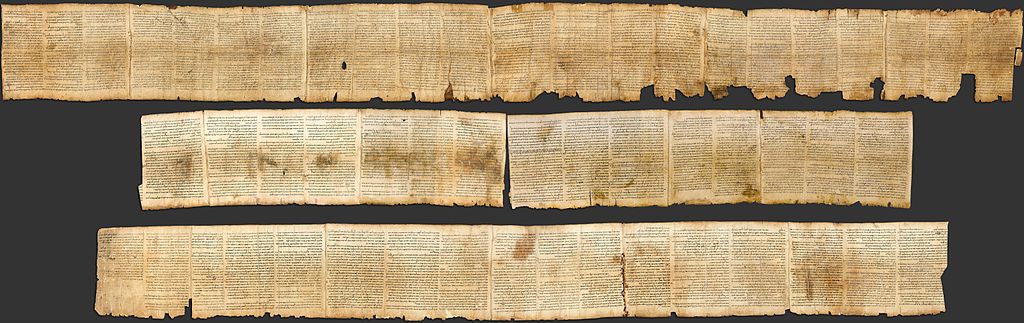

Great Isaiah Scroll. Photographs by Ardon Bar Hama, author of original document is unknown. (Website of The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

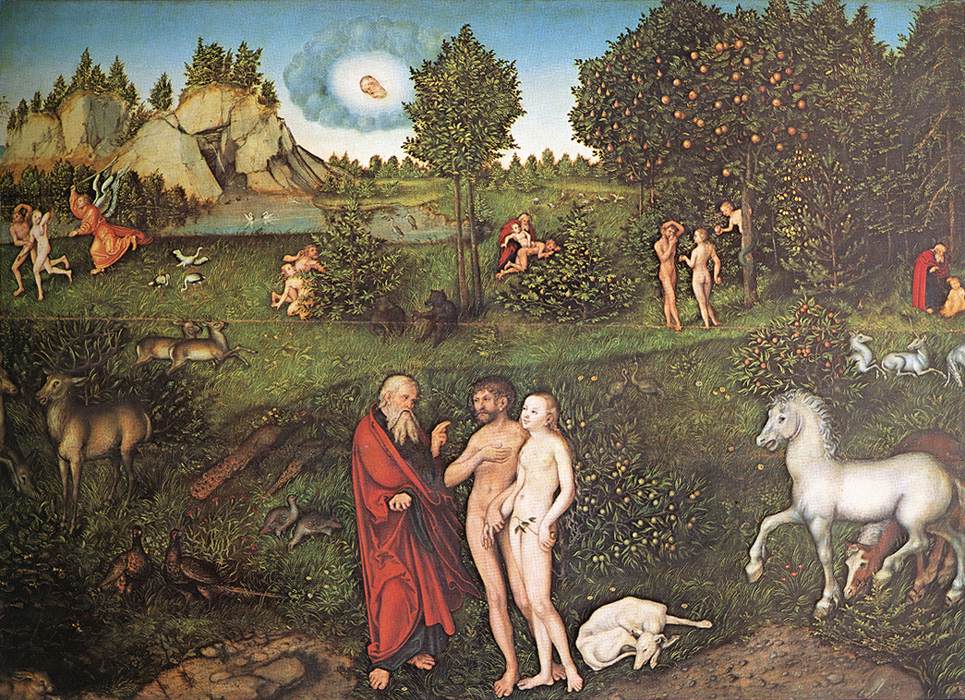

Most Biblical scholars think Genesis contains two separate creation stories, which were written by two different authors or sets of authors in completely different times and cultural settings. The first story is found in chapter 1, and uses the writing style of a priest. Water is described as a chaotic force, and humans are created after the chaos has been neatly ordered and life has begun. The second story is in chapters 2 and 3, where the man is created before life has sprouted on earth, and the woman comes into the plot much later on – before humankind begins to wreak havoc in Eden.

Garden of Eden by Lucas Cranach the Elder [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Adam Naming the Animals – Dublin Christ Church Cathedral North Aisle Window Cartooned by John Hardman Powell (1827–1895), executed by Hardman & Co., photographed by Andreas F. Borchert [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

A Christian idea of creation starts with creation from nothing, which works very well in a universe with a beginning. As Julie Andrews sang in the Sound of Music – “Nothing comes from nothing, nothing ever could”*. The creation story also gives an explanation for the effects of good and evil in the world. For Harris, this is the best evidence that theology might be onto something, because every person who has ever lived knows the reality of evil.

The story of ‘The Fall’ in chapter 3 of Genesis is often used to explain the origin of sin and death, and why we needed Jesus to save us. The idea that two people first sinned and we somehow inherit that sinfulness was made popular by early theologian Augustine of Hippo. He wanted to demonstrate how much we need God’s help – we cannot save ourselves. This interpretation may provide a seemingly simple answer to the problem of how suffering and physical death entered the world, but it has caused all sorts of problems for the acceptance of modern science. For example, there is plenty of evidence that death was occurring long before humans even came on the scene. Even if this was only about human suffering and death, there is no evidence that the human population ever narrowed down to two, or even a small group of people. These are just a couple of the scientific problems with Augustine’s view. But for Harris and many other Christian scholars, this is not the only possible – or even the best – interpretation of the text. This part of Genesis isn’t clear about how exactly sin or suffering entered the world. The Hebrew word that is interpreted “good” – and taken to mean perfect – in the account of creation can simply mean “it works”, or that it is fit for purpose. The rest of the Old Testament shows very little interest in the story of Adam and Eve, but describes the repeated cycle of disobedience and rescue by God that begins in Genesis.

Harris outlines four main ways of dealing with the fall and evolution. The first is to reject evolution, and hold onto a traditional notion of the fall as the first sin, that affected not just all human beings but disrupted all of creation, bringing in physical death and pain. Second, would be to reject this traditional idea of the Fall altogether, and hold onto evolution. Third, perhaps the Fall was a historical event and Adam and Eve were representatives in some way of humankind at a stage in history when humankind were beginning to become self-aware.

Stained glass By Handel, d. 1946[2], photo:Toby Hudson derivative work: CrazyInSane [CC BY-SA 3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

*Dr Harris didn’t use the Julie Andrews quote, but I’ve been dying to use it ever since I heard someone make the link between Big Bang cosmology and the lyrics of the Sound of Music…

Taking it further

- Mark Harris, The Nature of Creation: Examining the Bible and Science (Routledge, 2013)

- BioLogos – the website of a Christian organisation that supports both sincere Christian faith and mainstream science.

- The Faraday Papers – which include a number of commentaries on the Genesis story – especially the one by Revd Dr Ernest Lucas (no. 11).

- Test of FAITH – resources to enable small groups to discuss science-faith issues, including the interpretation of Genesis 1-3.

- Denis Alexander, Creation or Evolution: Do We Have to Choose? (2nd Edition, Monarch, 2014). A fairly in-depth look at the issue of whether a faithful reading of Genesis is compatible with current evolutionary biology.

- Ernest Lucas, Can We Believe Genesis Today? (IVP, 2001). An introduction to the main issues in interpreting Genesis, written by a biblical scholar who was formerly a biochemist.

- Darrel Falk, Coming to Peace with Science: Bridging the Worlds Between Faith and Biology (IVP, 2004) Falk’s own journey of reconciling Christian faith with science.

- http://www.cis.org.uk/resources/ (bottom of page), a number of organisations that support Christians who are scientists worldwide, as well as Christians in Science (CiS) itself in the UK.