The thought that God might have visited our own planet in human form is so mind-blowing that most people react in one of two ways: either to reject it as nonsense, or to try and understand how it affects us. At the Scientists in Congregations conference in August, Grant Macaskill, Professor of New Testament at Aberdeen University, spoke on a section of the Bible that is often used to think about how God relates to the world through his son, Jesus.

Colossians 1:15-23 describes Jesus as a mediator-figure. Using very grand language, this passage conveys the full reality of who Jesus was. Everything was created[i] through him and for him. He sustains the entire universe, keeping it in existence. He is God’s ultimate representative on earth, and the one to undo the effects of our fall from grace. He is the ultimate head of the church worldwide, and “in all things he may take the first place”. Jesus’ resurrection from the dead is seen by many as proof that these claims are true.

So the cosmos operates through one person – Jesus – and he enables everything in the cosmos to relate back to God. As Macaskill said, in order to grasp the full enormity of God’s incarnation, it is vital to understand Jesus’ role as mediator of everything. He simultaneously inhabits the created realm and the uncreated, because he has always been in existence.

The writer of Colossians draws parallels with the Old Testament and the Jewish Torah, in the way that they speak about wisdom. The divine attribute of wisdom was there in the beginning, and to live unwisely is to go against the grain of the world. Colossians subverts and reinterprets these themes: Adam was made to be wise “in the image of God”, but Jesus is “the image of God”. In other words, people somehow represent God, but Jesus is God, and the ultimate example of how to live well.

The ecological dimension of Colossians 1 comes in verse 23, which says that Jesus’ message affects every single creature on earth. In his book The Bible and Ecology, Richard Bauckham explains that Jesus is our fellow creature, not just our ruler and the one who holds everything together. This brings a shift in perception towards seeing ourselves as one kind of creature among many different creatures, and gives Christians a unique voice in the dialogue on science, faith and ecology.

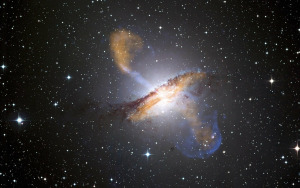

Copyright ‘Waiting for the Word‘. License: Creative Commons 2.0

Finally, because he was killed and came back to life, death is now part of God’s identity. Macaskill cautiously suggested that death need no longer be seen as a negative, but a necessary and natural stage in the existence of all things. 1 Corinthians describes Jesus destroying death through his resurrection, and Macaskill suggested a better translation might be ‘nullifying’. So Job’s death as “an old man, and full of days” (Job 42:17) might be seen as an intended stage on the way to resurrection, rather than an evil that could have been avoided if he had managed to live a perfect life.

I appreciated Macaskill’s humble reminder that in taking the Bible seriously, we need to avoid the danger of assuming our reading of the passage is decisive. If the Bible is nuanced and complex, we need to do it justice by attempting to understand all its complexities and interpret it in a nuanced way. So this view of spirituality, ecology and death is brought to the table for critique, and I’m sure that other Biblical scholars will have plenty to say on the subject in the coming years.

[i] Other posts throughout this blog explain how that could have happened slowly, using the processes of the Big Bang and chemical and biological evolution.