Whether Christian or not, scientists share a reverence for the moment when painstaking lab work blossoms into something almost transcendent. This post is taken from an article that I recently wrote for Third Way, and explains some of the thinking behind my current work on science and faith.

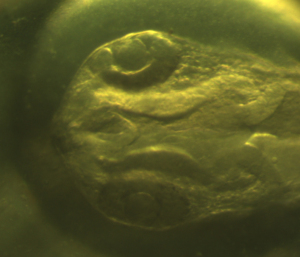

I’ll never forget my first sight of a Zebrafish larva. At twenty-four hours old they are about two and a half millimetres long and almost completely translucent. A simple low-magnification microscope reveals every detail of their anatomy in minute detail. You can see the heart pumping, and tiny red blood cells moving through capillaries. You can trace the outline of muscle fibres in their tails, and see every detail of the developing eye. Later on the eye becomes covered in silvery pigment cells, the transparent lens protruding, beautifully rounded and greenish in colour.

As a teenager heading off to university, I knew that science was compatible with Christianity – but I didn’t expect it to enhance my faith in the way that it has. I studied genetics because I enjoyed finding out how things worked. I was also attracted by the visual aspect of biology: developmental biology, for example, is essentially stories with pictures. There’s a huge amount of creativity involved in scientific research, and I loved the way in which problem solving and lateral thinking were an important part of my courses. I went on to earn my PhD by spending three years looking at how eye development in Zebrafish is affected by various environmental and genetic factors – and I never grew tired of looking at those wonderful organisms.

I wasn’t quite patient enough to stay in the lab long-term, but my experience as a working biologist showed me how complex the natural world is, and how privileged we are to understand even a tiny part of it. Ultimately it taught me how great God is. Any being who can create such a vast and beautiful universe is worthy of my worship.

When I left the lab I worked for the professional group Christians in Science, and was immediately involved in debates over creation, bioethics and the environment. If we evolved, how are we different from animals? Do we have a disembodied soul? If we’re getting a new earth, why bother with this one? These dialogues are important, and I spent several years addressing them in different contexts. Shortly after I began to work at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, Dawkins’ book The God Delusion was published and sparked a huge response. Some of the responses to Dawkins have been helpful, but I began to wonder whether we will ever be able create opportunities for a more positive dialogue.

I was challenged by something that the theologian Alister McGrath said in a video: ‘Christians who are scientists are always reacting…one of the big questions is, how do we begin to take charge of the cultural agenda…rather than continually respond to it?’ Christians working in science know first-hand that science enriches their faith, but their voices are not often heard. A large part of my current role as a Research Associate at The Faraday Institute is to start new conversations that show how science enhances faith.

Starting a conversation about science and faith in a positive way is difficult. I often have to delete the first few sentences of an article or the first slide of a presentation because I have fallen into the trap of using a negative hook yet again. It is very important to respond to the prominent media stories about science and religion being in conflict, but we don’t all have to – there are other ways to be culturally relevant.

The BBC makes science and nature documentaries that lift our spirits and reassure us that in between wars and ugliness, beauty and wonder still have a place. I have found that it is possible to start a dialogue on science and religion by relating the stories of scientists who find beauty, awe and wonder in their work. These experiences are common to all scientists, regardless of their beliefs. There is something here for everyone, both Christians who need to be encouraged that science does not threaten faith, and those who have not yet explored the spiritual side of science.

As for me, I still think Zebrafish are beautiful, and I feel privileged to know so much about them. How are these creatures part of the whole world’s worship of God? I’m not completely sure, but my study of them has filled me with awe. I am more able to appreciate God’s vast creation in all its intricacy, evolving and bursting with life.

This post is an extract from an article that was first published in Third Way magazine (April 2013), and is reprinted here with permission.