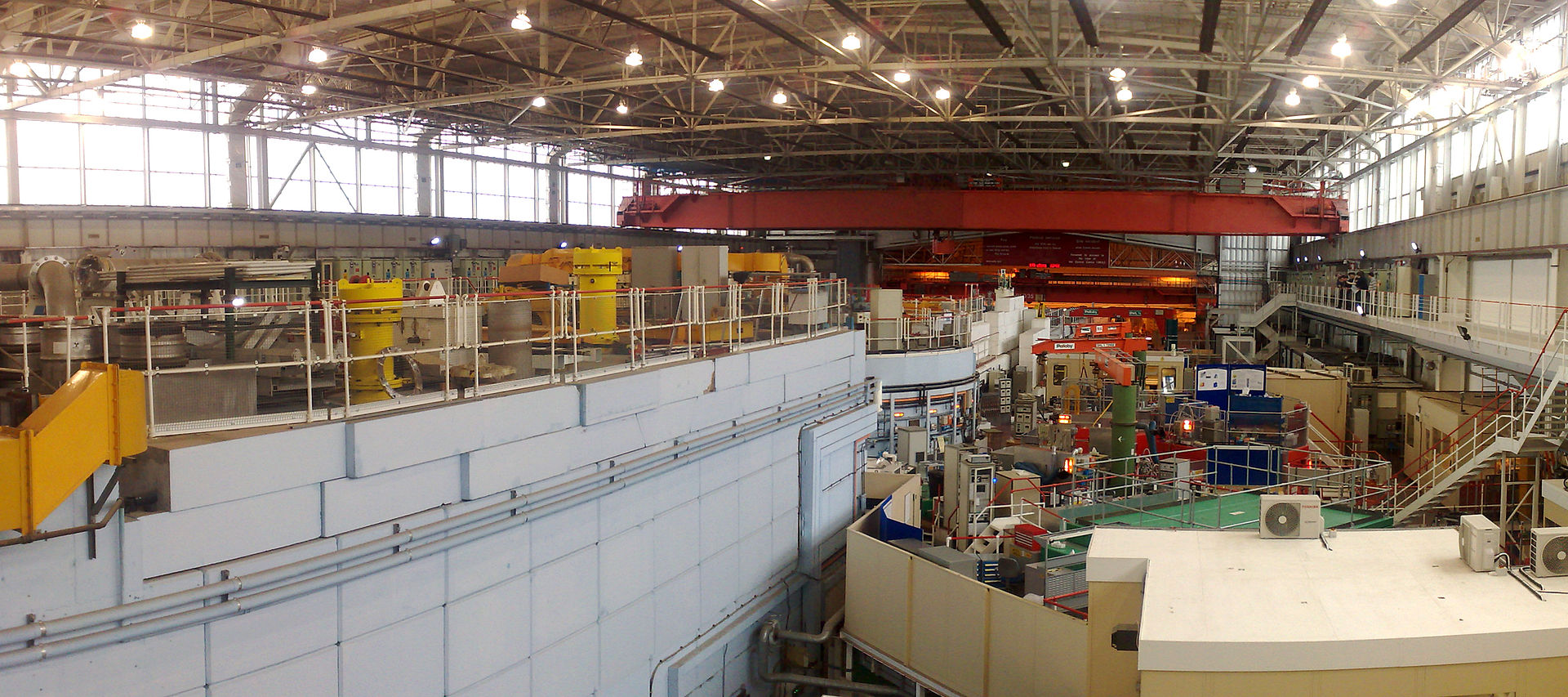

The opening speaker at last week’s Faraday Institute summer course was Mark Harris, Senior Lecturer in Science and Religion at Edinburgh University. He started by showing a picture of his two favourite workplaces. At the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in Oxfordshire he focused in on nature in its finest details, and at the Edinburgh Divinity School he’s now involved in looking up to the heavens and asking very broad questions.

Harris spoke about the relationship between science and religion, asking whether there is a clash of worldviews between the two. He started out by saying that both science and religion are almost impossible to define in general terms. Dictionary definitions of religion never seem to capture the experiences of ‘the other’, of community, or dealing with the hard facts of life that are so important for him in Christianity. Definitions of science are also slippery because there are so many different methodologies to include that it becomes difficult to summarise them in a meaningful way. This is reflected in his own view of science and faith, which he gave at the end of the lecture.

The most common models for the relationship between science and religion are conflict, independence, dialogue and integration. These were the four categories used by Ian Barbour, who was one of the founders of the field of science and religion. Conflict tends to be promoted by those who shout the loudest – the people whose agenda is to diminish the importance of the other side – whether it is science against religion, or religion against science. Independence was promoted by the late palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who wanted a clear separation between science and religion. Is this what is being embraced by some Christians when they say that science and religion are different sides of reality, or ask different types of question? Perhaps not, but this is one place where we need to be careful about the words and definitions we use.

Dialogue suggests that science and religion can learn from each other, as they did in the past when an education in natural philosophy (as science was called back then) was a step on the way to a career in theology. We still assume that there are laws in nature and that the world can be understood in a logical way, even though the theological arguments behind those things have been forgotten. So can dialogue still happen, building on this heritage?

The idea of integration probably sounds wacky to most natural scientists, but there are other ways of viewing science and religion besides these four. Perhaps a more helpful way of seeing the two might be complexity, which is based on the work of the historian John Hedley Brooke. In his book, Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives, he pointed out that science and religion are “social activities involving different expressions of human concern, the same individuals often participating in both”.

One of Harris’s favourite models for relating science and religion is what he has called prophetic conflict, based on the work of the philosopher Willem B. Drees. In Religion and Science in Context, Drees writes that the academic field of science and religion is a product of secularisation, and is driven by conflict – but conflict can sometimes be a good thing. He says that religion should have a ‘prophetic’ dimension, pointing to a better world and offering a critical perspective. If religion holds science to account in a healthy way, conflict is inevitable from time to time.

For Harris, science and religion cannot be neatly pigeonholed into a single model. Our views may change many times over the course of our lives (Darwin’s certainly did!), and different aspects of science and religion may also relate in different ways. He started his lecture by talking about worldview, or a personal philosophy of life. For him, the doctrine of creation makes sense of both science and religion. If the world had a beginning, if it was made from nothing, and if it relies on God for its continued existence, then all the sciences have the same starting point. So although our views about the relationship between science and religion may be constantly changing as we go through life, this may be a way of bringing them all together and making sense of them.

Other Faraday summer course lecture reports will be featured in the coming weeks. Videos and audio recordings of the lectures will be appearing on www.faraday-institute.org as they become available.