December sunrise in Perthshire, © R Bancewicz

A stunning sunrise is a welcome gift in midwinter. I hauled myself out of the house around 7.30am one January day, trusting that a run would wake me up after a bad night. As I reached the guided busway, which cuts southeast through our side of Cambridge, I was rewarded by a grand display of reds and pinks. No doubt others were grinning too – an injection of beauty to fuel their commute. My route took me away from the light, but when I turned around and zigzagged back through the woodland by the side of the path I could still glimpse some lingering pink on the horizon.

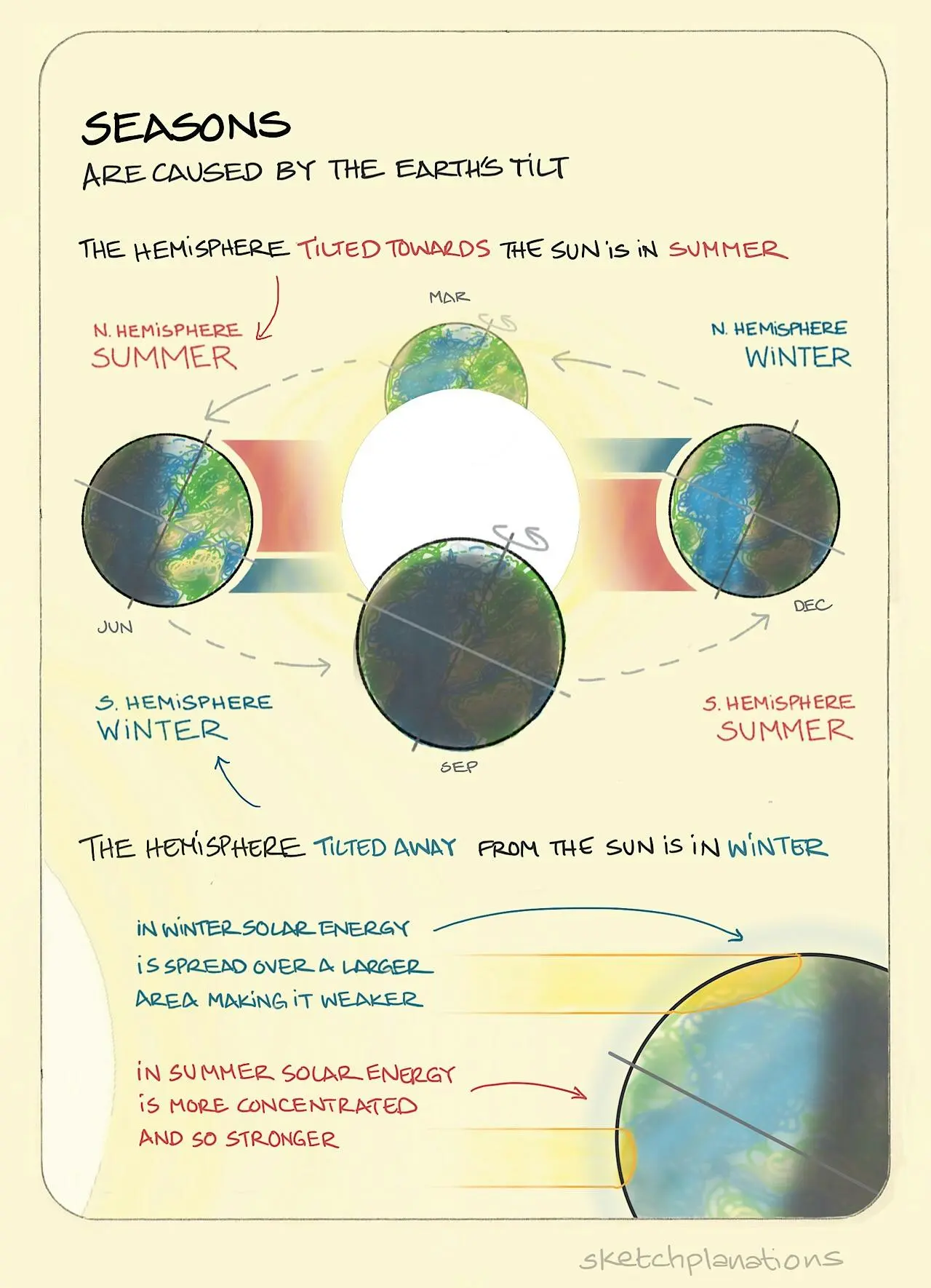

Image: Jono Hey, sketchplanations.com

It’s not just that we’re looking for ways to lift our spirits or more likely to be awake, sunrises and sunsets are measurably more striking in winter. Cooler weather means less water evaporation and therefore less humidity blocking the light, so on dry days we can see vivid colours. The atmosphere filters out greens, violets and blues in the sun’s rays. When light hits the earth at a sharper angle in winter we get even more of that filtering effect to highlighting reds and oranges. The sharper angle also means that it takes the sun longer to rise or set, giving us more time to enjoy the show.

It’s easy to forget, warmed as we are by the gulf stream, that the UK is at the same latitude as Labrador. No wonder we can feel sluggish or succumb to infections when we are getting as much sun as a place where snow is on the ground for eight months of the year, and the sea is frozen from January to May.

Your body clock can get a bit messed up when you get less than eight hours daylight, or less than seven if you live in Aberdeen. Perhaps you are affected by Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder, so called because you struggle to go to bed at time at a time that allows you to get enough sleep before you have to leave for work in the morning. Less common is Advanced Sleep Phase Disorder, when sleep drives kicks in part way through the evening then evaporates at an inconvenient time such as four or five in the morning. Either can make life harder in a society that assumes the same fairly regular daily schedule of work, socialising and rest regardless of the season.

Given the temptations and pressures of modern urban life, it’s not surprising that there’s a huge emphasis on wellbeing, with advice, therapists or groups to help us develop habits that make us thrive. It’s striking how many of these services help us access things that are essentially free (or in the case of work, should hopefully pay): sleep, fresh air, daylight, exercise, relaxation, learning, meaningful occupation, conversation, friendship, love. We just need to show up and learn how to make the most of it.

The day I ran was the beginning of a module in my part-time theology course on the theology of Paul[1], whose lyrical treatment of love will be read in thousands of churches around the world on Sunday (as well as on wedding days throughout the year!)

“If I speak in the tongues of humans and of angels but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers and understand all mysteries and all knowledge and if I have all faith so as to remove mountains but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions and if I hand over my body so that I may boast but do not have love, I gain nothing.”

1 Corinthians 13: 1-3

Gripped by winter tiredness and spiralling thoughts, an ethic like this seemed totally unreachable. But that sunrise said, it’s not all about me or my capacities, everything I need is already there. The previous chapter in 1 Corinthians is about spiritual gifts. Love for others is something I can ask for again and again.

What I have subsequently learned scientifically about the vividness of winter sunrises and sunsets has helped me to appreciate that gift even more. Embedded in a cold dark time is a regular source of light and colour, totally free and available to anyone who can see it. I will get bogged down and make a lot of mistakes, but that’s not the point. When I show up I will be met with grace.

[1] i.e. The one to whom half the New Testament is attributed.