Can faith actually feed into and help science? This was one of the questions that David Hutchings and Tom McLeish asked as they wrote their book, Let There Be Science, which was published by Lion last month. David is a physics teacher based in York, and he teamed up with Professor McLeish (author of Faith and Wisdom in Science) to explain what science is, what it’s for, and what does Christianity have to do with that. In today’s podcast (abbreviated transcript below) I asked David about the creative side of science.

Can faith actually feed into and help science? This was one of the questions that David Hutchings and Tom McLeish asked as they wrote their book, Let There Be Science, which was published by Lion last month. David is a physics teacher based in York, and he teamed up with Professor McLeish (author of Faith and Wisdom in Science) to explain what science is, what it’s for, and what does Christianity have to do with that. In today’s podcast (abbreviated transcript below) I asked David about the creative side of science.

We’re really glad you’re here David, and we’re going to be talking about questions, but first I gather you want to tell us about a levitating frog?

Yes, it goes back to Andre Geim, a physics professor at Manchester University and Nobel Prize winner in 2010. He also won an Ig Nobel – prizes for amusing or slightly bonkers science – after he had spotted adverts for little magnets that you could attach to taps to stop lime scale. Like all good scientists he was pretty sceptical, so he decided to investigate. He found that we didn’t know much about the relationship between magnetism and water. So, in his own words: “I poured water inside the lab’s electromagnet when it was at maximum power. Pouring water in one’s equipment is certainly not a standard scientific approach. I cannot recall why I behaved so unprofessionally… as a result we saw balls of levitating water.”

Frog diamagnetic levitation By Lijnis Nelemans [GFDL or CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

You had another story about someone who solved a problem with a really ingenious solution?

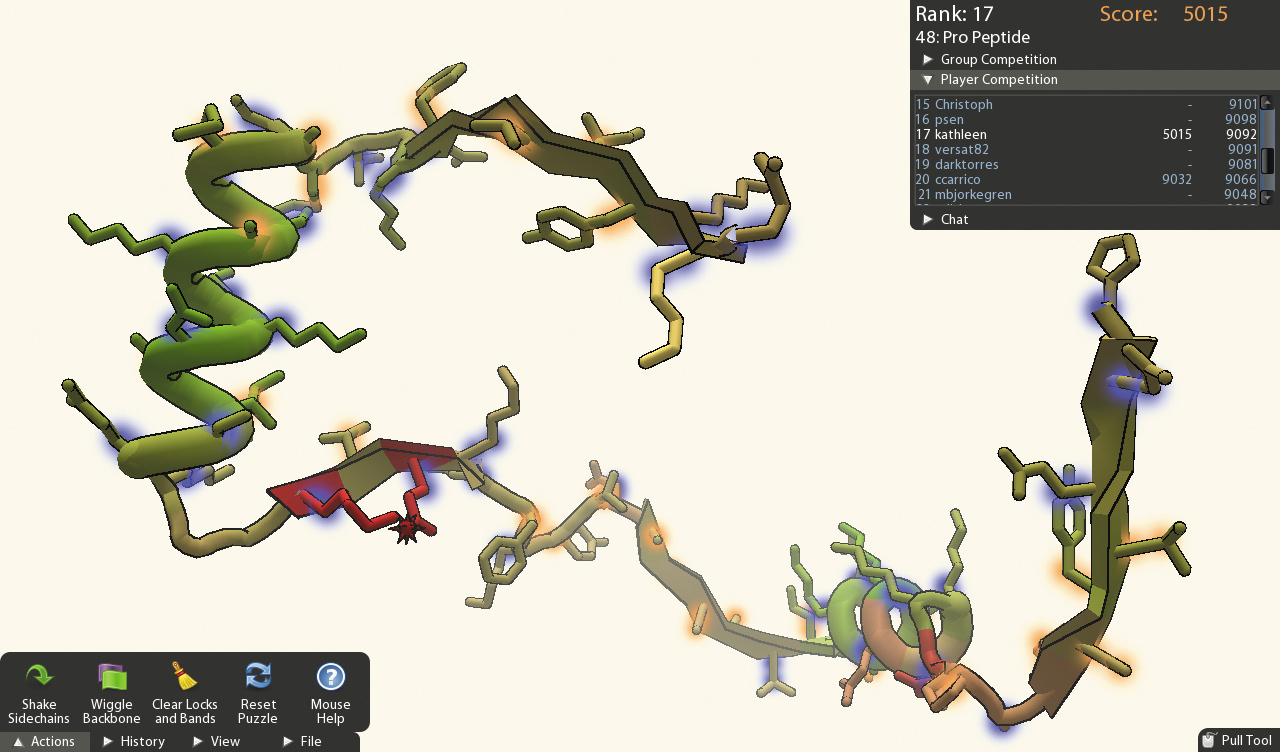

This was a similar case, but to do with proteins. Amino acids are quite small, just collections of a few atoms, but if you start sticking them together into long chains you end up with proteins. If you want to know what proteins do you have to know how they fold up into incredibly intricate patterns based on the charges and the different arrangements of atoms. This was an issue that David Baker, a biochemist at the University of Washington, was working on, but it is notoriously difficult because a protein can fold in millions of different ways. It sounds like a job for a computer, but there are some things that human beings are pretty good and yet computers struggle with, and a lot of that can be to do with image manipulation. This protein problem turned out to be similar. That is when you get this brilliant question from him that unlocks a whole new field: “what would happen if we turned protein folding it into a computer game?”

Foldit PD002: Figure 1.1 By Rosenfield Media. Flickr. (CC BY 2.0)

So he got in touch with his computer science friends, and they made a game called ‘Foldit‘, where you scored points for how well you folded proteins based on known chemical properties. They released it for free online, and the results were far beyond what they could have imagined. In one case they were looking at the structure of an AIDS-related virus which had been unsolved for 15 years, but gamers solved it in 10 days. Teenagers were doing science that the pros in the labs were struggling with.

So this seems to be about people who ask questions no one had thought of before?

Yes, there seems to be a pattern throughout the history of science. What makes a difference to scientific progress is when someone asks a really good question. Einstein said that, as far as he is concerned, the big difference between him and a lot of his colleagues who didn’t make the same progress was that he never stopped asking questions.

You and Tom are both Christians, so can you talk a bit about what faith has to do with that? There is this point of view that faith is about just believing and you almost turn the questions off, because if you ask too many it will fall apart.

Yes, that is exactly what A.N. Wilson said. He is a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and he wrote a book called Jesus in 1992 where his argument was essentially: “this is clearly just a guy, he’s not God, there’s a lot of mythology around him.” One of the accusations he makes about Christianity is that when Christians start thinking about Jesus, things start breaking down and they lose their faith. To be fair, I think you will find Christians who do think like that. But what I think is important when we’re asking about Christianity is to say “what about Biblical, historical Christianity?”

So what did you find from looking at the way questions are asked in Bible?

Doing this research for the book showed me there was even more questioning in the Bible than I had thought. There are 1200 chapters in the Bible and 3300 questions. What is particularly interesting is that a lot of them are questions asked by God, and by Jesus. Then you have to start thinking “why are those questions there?” Surely they cannot be there because God needs information, because the Bible consistently presents God as all-knowing. So if he already knows everything why is he asking the questions? You could say the same with Jesus, because the New Testament presents him as God.

Public Domain, via Wikimedia

I think one of the key breakthroughs there is to understand that that questioning is there to encourage us to think about the answers and ask those questions for ourselves. Jesus asks, “Why are you so afraid?”, “Why do you entertain evil thoughts in your heart?”, “Why did you doubt?” Of course the most important one of all is, “Who do you say I am?” Christianity has got this questioning riddled all the way through it.

There are also long passages where people ask questions of God. Again, if the teaching in Christianity was “Don’t ask questions, you just believe!”, we would not expect to see any dialogue. But we don’t see that. When people ask God questions in both the Old and the New Testament, he interacts with them. He will answer them, or he’ll ask another question back, but there is interaction there and that is how you encourage questions.

From my looking at it, the message of the book as a whole seemed to be that Christianity has played a vital part in the development of science, so science is something Christians should be doing today. Is that a fair summary?

Yes, I think that is definitely one of the major threads running through the book. I would say that overall, what we’re trying to draw attention to is that the core principles in Christianity will produce good science. For example, Christians have been encouraged by the Bible to ask questions, and we’ve seen that is great in science. Other examples would be the notion that we have been made with a mind that is in some ways similar to God’s (we’ve been made in the image of God). God’s mind conceived the universe and brought it into being, so if that is replicated in us to a certain extent, then there is that capability for us to understand the universe. There is a resonance between those minds where the same sort of patterns that God put into place make sense to us. We look at examples in our book where again and again people have intuitively found answers to very deep mathematical realities about our universe – and sometimes they’ve been doing it when they’ve been playing around.

So you have mapped out a very positive relationship between science and faith, and it sounds like the book will be incredibly helpful to people who are scientists, as well as people who are not. Thank you very much Dave, for talking to me today.