Scientists experience awe in very different ways, depending on the systems they study. In the second part of my interview with Spanish Palaeontologist Fernando Caballero Santamaria, he describes how he processes his experience of awe in his own work. (Part 1 here)

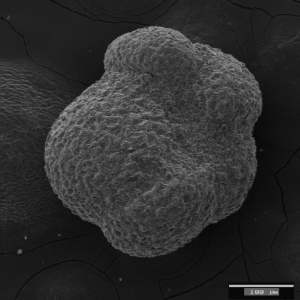

When you work with stones, as I do, sometimes it’s difficult to feel the sense of awe that more biological scientists often talk about. But when I’ve finished cleaning up my specimens and look at them under the microscope – that’s when I see real beauty. One of the greatest experiences of my career was when I was working with an electron microscope. The magnification was so high that I could see fossilised nano-plankton sitting in the pore of another plankton that I was studying. They’re so small, and so beautiful!

Outside of the lab, I often experience awe when I look at geological landscapes. For example, there’s a spectacular glacial valley in the Ordesa National Park in Northern Spain. Standing at the top of the valley, I have fossils under my feet, and in the distance I can see the limit of the Palaeocene period, the Eocene period, and so on. In my mind’s eye I am able to follow a three-dimensional reconstruction of these rock layers all the way to France in one direction, and towards what used to be the sea bed in the Basque country (where I live) in the other. It’s breathtaking. I’ve had similar experiences in Yellowstone National Park, and in Shark Bay in Australia where I studied stromatolites. To be there, just walking among the fossils…those are great experiences.

When I see a fossil, or when I am on top of a mountain looking at beautiful landscapes, I always think, ‘Grace to God’, because it’s his creation. I have no problem with saying that God is behind what I’m seeing, in the same way that I have no problem in saying we receive food from God when I understand how the water cycle and other factors produced it. By faith I believe that God created the natural laws that produced the geological structures I see.

Spending time in such awe-inspiring landscapes makes me think about how great God is and how small we are. My scientific studies have made me aware of how flawed I am. I move from the ecstasy of seeing the beauty of creation in the field, to being painfully aware of my faults. That duality is important to me. Sometimes I come home from a glorious experience at the top of a mountain, and I’m emotionally floored – conscious of my inability to live well unless God helps me. To be honest, I must deal with this confrontation every day. It’s not at all easy to be a Christian and a palaeontologist.

In the dedication at the end of my PhD thesis I wrote, ‘Soli Deo Gloria [Glory to God], because He was the one who said that the stones will speak‘. After my thesis examination we had an informal lunch with the examiners, and the conversation centred around this quote. All the people there were asking me, ‘What do you think?’ or ‘What do you believe?’ One of my examiners was very confrontational with me, because he couldn’t understand how a scientist could believe in God today. Later on, one of the other examiners wrote to me. At first I was afraid that he was also upset with me, but he said, ‘To your ‘Soli Deo Gloria’, I say ‘Magnus in magnis, maximus in minimis‘’, which is a quote from Augustine: ‘God is great in the big things, but is greatest in the small things.’ I was very surprised that he should encourage me in this way, because he was not a religious man. At the time he was the Chairman of the stratigraphy sub-commission of UNESCO. It was strange that this person who I admired scientifically thought the same as me: that these small fossils are so great, and reveal something about God.