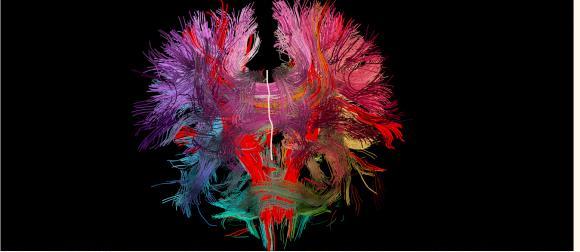

Cropped from Two-dimensional brain. Copyright: Radu Jianu/Brown University

Have you ever had that slightly disturbing experience of arriving at work and realising that you have very little recollection of how you got there? The human brain contains around 100 billion nerve cells[1], each of which makes multiple connections. This biological hardware is used to integrate signals from our own bodies and surroundings, as well as our memories and predictions for the future. Most brain activity actually happens without our being aware of it – our consciousness only needs to get involved when the outcome is not determined. In other words, the more routine our actions become the less we need to think about it.

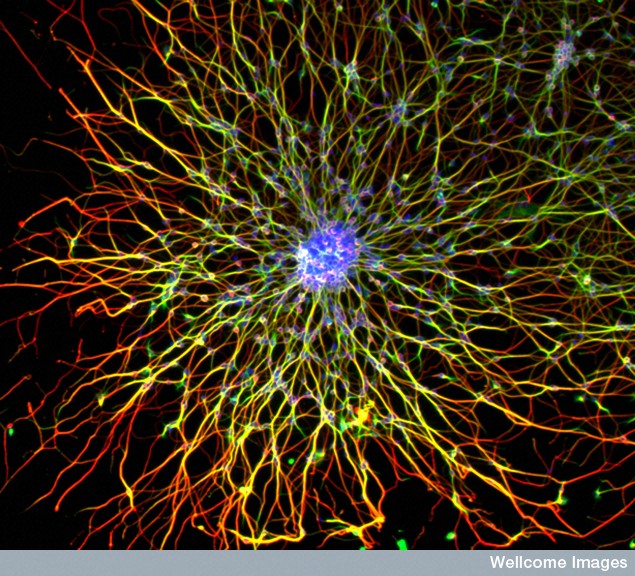

Neurons in culture. Credit: Ludovic Collin, Wellcome Images. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

This brief insight into the workings of the brain was part of Harvey McMahon’s recent Cambridge Paper, “How free is our free-will?”

For McMahon, our choices are made within certain boundaries. Some decisions do seem completely free: what kind of tea to drink just now, whether to go and speak to that person over there, or what to do about an out-of-the-blue job offer. Some of these choices are more important than others, but each time we feel we are making a completely free decision.

Pixabay – CC0 – Public Domain

Most decisions, however, are affected by our choices from the past. If I choose to have my hair cut short today, I cannot wear a ponytail tomorrow. My choice at the hairdresser’s has constrained my choice of hairstyle quite drastically. Our choices are also limited by events outside of our control. These involuntary constraints can include our genes, the family and culture we were born into, and certain aspects of the environment we live or have lived in.

The result of these interacting factors is that I make choices, but within limits. I cannot choose to be six foot tall, but I can wear a pair of heels. I find it hard not to eat sweet treats all at once, but I can choose not to buy them. There are also plenty of grey areas here. What if I don’t know that a certain choice will have long-lasting consequences down the line? What if I didn’t consider a decision carefully enough and it had unintended consequences? What if my ability to think is hampered by factors I am not aware of?

There is also the potential for change. We are influenced by our past, but not determined by it. At any moment I can decide to break a habit, or learn something new. This takes effort, because I need to consciously change my learned behaviour or do something completely new. Conscious thought uses more brainpower and takes more time, so I would have to give up thinking about other things and focus on this new resolution for a while.

Learning new things involves making new connections, known as synapses, between nerve cells. These connections fire off electrical signals which travel to other parts of the brain. As a synapse is used regularly, changes in its biochemistry take place which make it fire more easily. This ‘plasticity’ means that our choices can alter the makeup of our brains. Within the limits of our circumstances and past choices, we control our own destiny.

A biblical perspective adds some other factors into the mix. Yes, we are responsible for our choices, and that ability to choose is a gift from God. Our activities are also bounded or constrained by the will of God who is in ultimate control of all things. Some Christians believe in ‘predestination’, which is the idea that God pre-ordains everything that happens in the world. This strand of theology might seem incompatible with freewill, but McMahon is happy to accept that we make choices within the limits that are set by God.

Finally, this process does not happen in isolation. I can choose to change my environment, including the people I interact with, thus changing the signals that my brain is constantly receiving. Anyone who has struggled to change a habit will know the value of a peer support, church or other community group. As shared values emerge, each member of that community becomes more than just an individual.

Finally, this process does not happen in isolation. I can choose to change my environment, including the people I interact with, thus changing the signals that my brain is constantly receiving. Anyone who has struggled to change a habit will know the value of a peer support, church or other community group. As shared values emerge, each member of that community becomes more than just an individual.

For Christians, the primary choice is to have a relationship with God. We are invited to “be transformed by the renewing of your mind” (Romans 12). This happens at an organic level, as our habits and attitudes change, but also at a spiritual level, through the work of the Holy Spirit. As Harvey writes, “These are aspects that are beyond the scientist to precisely understand, but as with dark matter, there is more to the story of how the mind works. We are left in no doubt that change is a two-way experience: God works in us to change us and we must at the same time make every effort to change ourselves.”

So according to McMahon, freewill flourishes within constraints. It is an essential part of our humanity, and a Christian worldview can add to that, bringing “a fuller understanding and experience of freewill … we can be no happier than when we are acting as [God] would have us act within the limits of the world in which he has placed us.”

The Cambridge Papers are a series of briefings on issues from a Christian perspective. You can find them all on the Jubilee Centre website.

[1] Compared to a mouse’s 100 million

© Ruth Bancewicz, Nigel Bovey

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth arrived at The Faraday Institute in 2006, and is currently a trustee of Christians in Science.