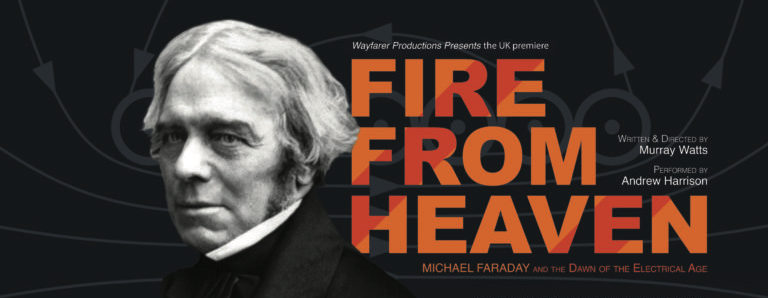

This excellent and thought-provoking one-man play looks at the life and work of a scientist who, despite all his efforts to avoid fame and fortune, is well known even outside scientific circles. The playwright, Murray Watts, has also written a number of screenplays, and his best-known production is probably the animated feature film The Miracle Maker (2000). He is also known in Christian circles for his involvement in the Riding Lights theatre company.

I had the privilege of being at one of the premier public performances in Oxford last month. Andrew Harrison played Faraday and a number of other significant characters in his life – including his wife Sarah, his mentor and employer Humphrey Davey, and Davey’s aristocratic and jealous wife – convincingly, and with an energy that had me gripped for the full 75 minutes of this one-act show.

The play begins with Faraday as a lowly apprentice bookbinder, hungry for knowledge about ‘natural philosophy’, as science was then known. A kind customer sees his potential and offers him a ticket to a lecture by Humphrey Davey at the Royal Institution.

Harrison drew a good amount of laughter from the audience throughout the show with his portrayal of the gruff and snobbish treatment Faraday received over his lifetime by certain members of the scientific establishment. Faraday’s dogged perseverance and love of science enabled him to keep going in his experimental work, even when he was at times prevented by his employer from pursuing avenues that really interested him. His brilliance eventually won him the respect of his colleagues, and a place in the establishment that initially assigned him a role as a bottle washer.

Faraday was a dedicated member of the Sandemanian Church – a very small non-conformist denomination which focussed on fellowship and reading of Scripture. He said very little about his faith publicly, but was known to have declined a knighthood, the presidency of the Royal Institute, and the presidency of the Royal Society (twice) because his faith taught him to avoid accumulating wealth and honours. Watt’s treatment of Faraday’s life highlights what we know of his faith, showing that he considered science as a serious and worthwhile calling for a Christian.

Memorable moments in the show for me were when Faraday’s growing scientific fame was pitted against Davey’s growing jealousy; the sadness caused by Faraday’s childlessness; the first Royal Institution Christmas lecture on the chemistry of a candle; and Faraday’s excitement at the potential of electricity to change the way we live.

This play is an excellent portrayal of a rising star in the scientific world, the pitfalls and opportunities he faced, and the ways in which his faith formed a firm foundation for it all. I would recommend it to anyone who wants to think about how science and faith interact, as well as those who are simply curious about science, or human nature. Although intended for an adult audience there is nothing in this production that is unsuitable for children, and I expect that some older teenagers might well appreciate it.