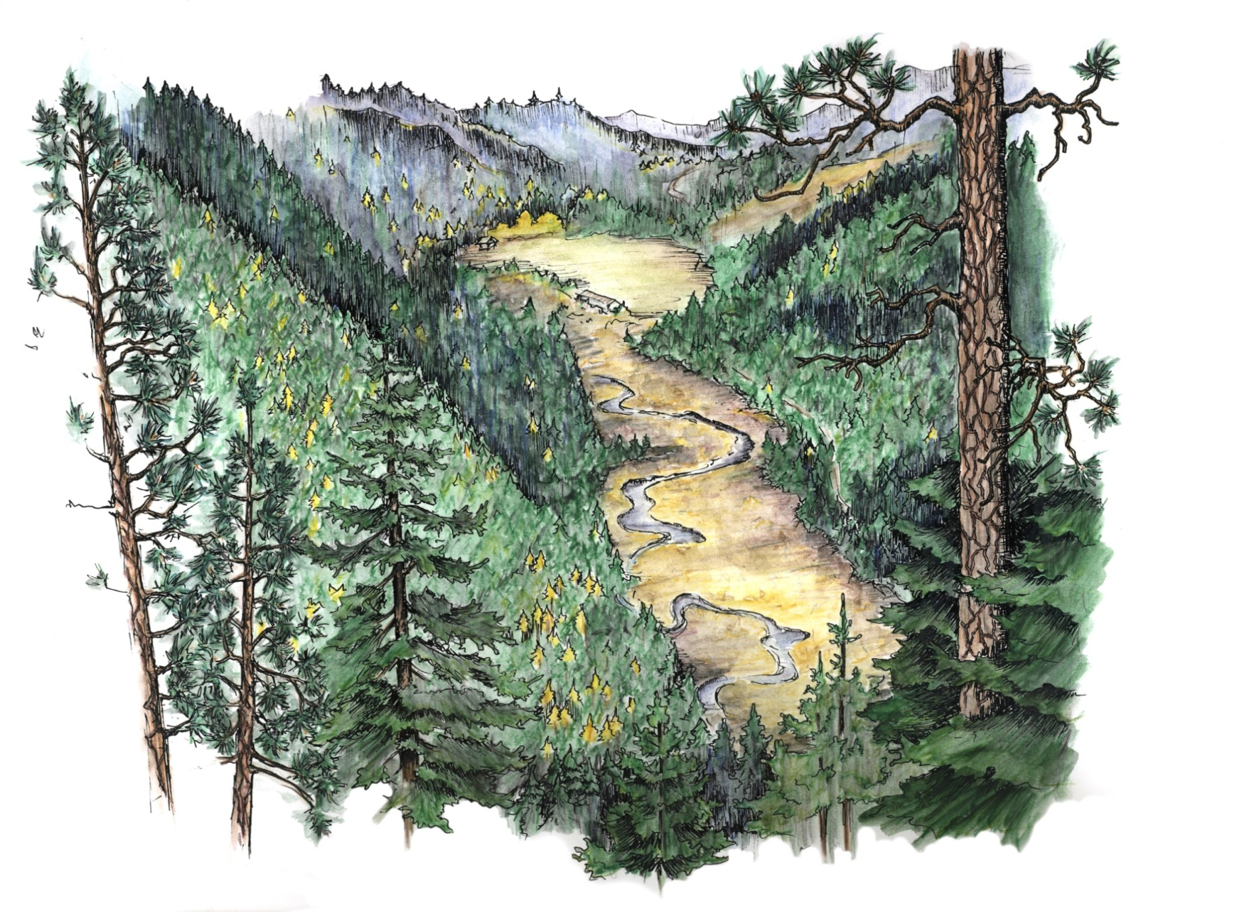

© Lauren Stark Adams of Spokane, Washington

What is our place in the world? In his seminar at the Faraday Institute last month, Dr Jonathan Moo described the current movement towards ecomodernism, which involves a separation from nature. If you want to understand this trend in more depth you can listen to the recording of Jonathan’s talk. In this post I will focus on the last part of the seminar, where Jonathan presented his own ideas about how limits can help us to flourish.

Jonathan Moo

As an Associate Professor of New Testament and Environmental Studies at Whitworth University in Spokane, Washington, Jonathan has a fairly unique experience. Once a year he leads a field trip into the mountains, teaching the students about the environment they see and also giving them a biblical perspective on creation. This is a situation where science and faith complement each other very well– understanding the long slow processes of how such diverse and beautiful surroundings can come about, and also learning something about the God behind it all.

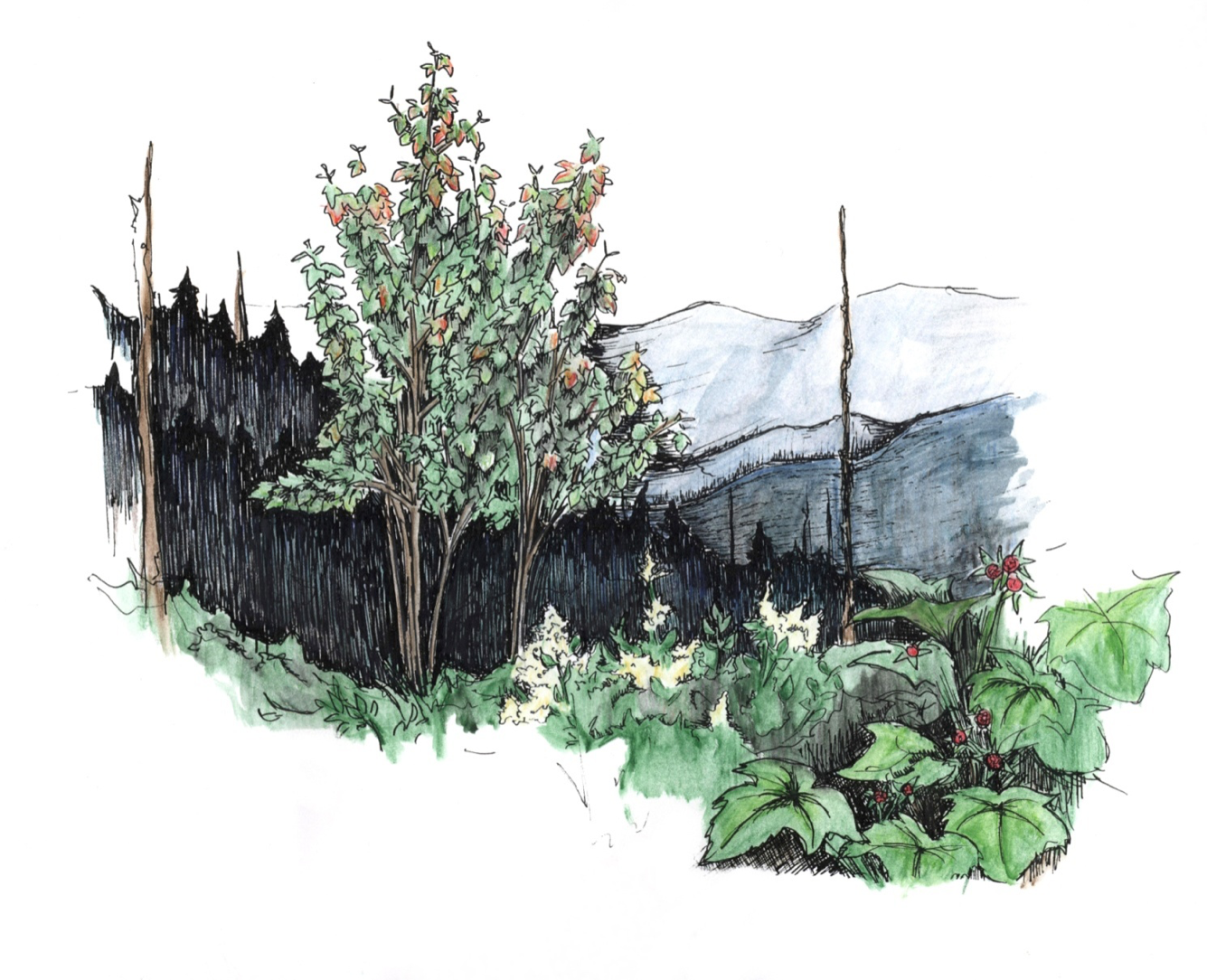

© Lauren Stark Adams of Spokane, Washington

In his latest research, Jonathan’s aim is to ask questions about our assumptions about the world, and offer some ideas about what it might look like to flourish in a sustainable way. Christian faith brings some unique perspectives to this discussion, not just for the Christian community, but also for others who are looking for ways to find meaning and purpose in the world. This work is at least partly inspired by the American writer and environmentalist Wendell Berry, who suggested that “what is good for the world will be good for us”.

The biblical narrative is that human beings are creatures made ‘from the dust’, and we will return to the dust when we die. We belong to creation, to each other, and to our own bodies. Embracing those things and their limitations as a gift given in love will help us to find our own sense of belonging, and learn to love and honour God.

In the creation stories of Genesis, Job, and the Psalms, God sets limits that distinguish one part of creation from another. Everything has its identity – including human beings – and takes its place in the cosmic choir. The ultimate purpose of creation is to worship God. Even the mythical Leviathan, formed by God to play in the sea, has its place in Psalm 104. “In wisdom [God] made them all.”

© Lauren Stark Adams of Spokane, Washington

When God stepped into creation as the person of Jesus, he took on the limitations of flesh and blood. Amazingly, God chose to reveal himself by taking on a human form. Jesus’ mission was to restore the relationship between humanity and creation (a project that is on-going) and point the way to God’s future peaceful kingdom. One of the messages of the New Testament is that this promised place is a material reality, where a full relationship will be restored between God, humankind, and the rest of creation. To be a Christian is to belong to Jesus, so we can belong even more to our own bodies, to each other, and to all of creation.

The biblical story gives humankind the unique role of ‘working’ and ‘keeping’ the land where we find ourselves. We serve God by caring for his creation, not by stripping it bare and driving ourselves into the ground in the process. The cycle of weekly rest days, fallow years for the land, and Jubilee years (when debts are forgiven and land given back to its original keepers), were a reminder to the people of Israel that the world doesn’t revolve around them. Work is good, but these limits are also a reminder that work is not an end in itself. The land belongs to God, and he is the one who ultimately provides for people and all the rest of creation.

God’s economy is based on abundance, not scarcity. Members of the New Testament churches voluntarily limited their own wealth and consumption so they could share with each other, sending financial gifts to places where there was famine – because there was enough to go around. Even when food was plentiful, such as in the story of the feeding of the 5,000, this good gift was not wasted. The leftovers were carefully gathered up.

© Lauren Stark Adams of Spokane, Washington

To find our place in the world there must be a reordering of desire. We will never be fully satisfied with the material things we have. But by accepting the limitations of our bodies, our relationships, and the rest of creation, we can set ourselves free to find true joy and abundance in other places. Exercising restraint in our behaviour and consumption lets us loose to explore things that are more satisfying – whether relationships, time to reflect, or other activities. In the Gospel of John Jesus says that he has come so that his followers “may have life, and have it to the full”, and that is the vision than Jonathan hopes to communicate in his research in the coming years.

Further information

- Listen to Jonathan’s Faraday Seminar, Transcending Nature? Christianity and Ecomodernism

- Jonathan Moo & Robert White, Hope in an Age of Despair: The gospel and the future of life on earth (IVP, 2013)

© Faraday Institute

Ruth Bancewicz is a Senior Research Associate at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where she works on the positive interaction between science and faith. After studying Genetics at Aberdeen University, she completed a PhD at Edinburgh University. She spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology at Edinburgh University, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. Ruth arrived at The Faraday Institute in 2006, and is currently a trustee of Christians in Science.