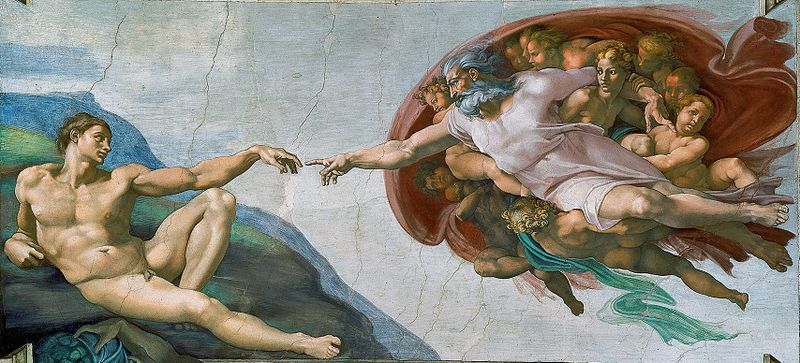

by Michelangelo [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Where did your interest in science and faith come from?

I was not much of a science student when I was in school, but as a graduate student I was doing philosophy. At that point I was reading a lot on anthropology – both cultural and paleo-anthropology – the history of human evolution and so forth, and I got very interested in that. My studies of the Bible are focused on creation, and once you start thinking about creation it opens you up to being interested in God’s world and how it works. I think that’s really where my interest in science comes from. In recent years I have been asked by Christians to make connections between what I study in the Bible and contemporary science, so I have been thinking about it more explicitly of late.

One of the things you’ve been looking at recently is what it means for evolved beings, which is what I believe we are, to be made in the image of God. Can I ask, first of all, what does ‘image of God’ mean? It’s a strange phrase.

It only occurs a few times in the Bible, in Genesis 1, 5 and 9, and then a few times in the New Testament. Most of the New Testament uses either say that Jesus is the image of God or that the church is renewed in the image of God.

Imagine that there is an underground river flowing and you can’t see it, but there are a few places the river comes to the surface and you can see the water. The image of God is the few places where the river comes to the surface, but the underground river – which is how the Bible understands what it means to be human – I think is pervasive throughout scripture and quite consistent, and it’s crystallised in the phrase ‘image of God’ a few times. That crystallisation helps us to understand it, because what was an image of a god in the ancient world which Israel lived in? The image of God was a statue you put in a temple and you believe that God, or whatever deity you worshipped who was present in heaven, somehow channelled his presence through the statue to the worshippers.

By analogy, the Bible assumes that the creation is God’s temple and God is in the holy of holies in heaven, and we are his image on earth, meant to manifest and channel his presence in all we do. So all of life is meant to reflect or refract the light of God into the complex world in all that we do, including science. The image of God is really about how we represent God in the world. You realise now, what Jesus meant in the parable of the sheep and the goats when he said ‘if you did it to the least one of these you did it to me’, because each one is representing God. So you do it to an image of God, and you do it to God.

The Proverbs have this saying that ‘anyone who abuses the poor insults their maker’ – that’s an image of God idea too. The Bible simply understands that humans represent God in the world. Either we do it well, or we do it badly. We have certainly done it very badly. We have shut off the world from God’s presence, in some sense, and Jesus opened up the path again. The church is meant to manifest what it really means to be fully human, redeemed humanity.

Before we get to science and faith working together, are there any wonders there for you in our evolutionary past?

Cropped: The Forest Ferns by Okinawa Soba (Rob) Flickr. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

It’s amazing to me how evolution works. What seem to be random changes over time result in new species, species with new abilities, new ecological niches, and so forth. I find that just thinking about the contingent changing world is a wonder to me, not just about human evolution but about all the complexity of creation. My creation theology from the Bible allows me to glory in the finicky little details of creation, the fractal nature of leaves, the complexity of islands… You can never measure the boundaries around an island, it is almost infinite. It’s an amazing thing that when you go to a microscopic level, you never find a straight line in nature. I am fascinated by that. I think that is part of the glory of God’s creation.

Putting the two together – the excitement about evolutionary biology and also this very real sense of being made in the image of God – how does that relatively recent story of us being evolved affect how we see ourselves and our relationship with God, for you?

Pexels [Public Domain]

The last thing I’ve written was an essay for Hilary Marlow, who works here, for a book she’s writing and it was called ‘The image of God in an Ecological perspective.’ What I looked at was how the image of God suggests both that we are distinctive, with unique gifts and capacities and we’re meant to impact the world by representing God in the world, but every time the image of God idea comes up in the Bible it also suggests we’re part of a bigger creation. We’re interdependent with that creation. So we exist only because we are part of something bigger, yet we have a distinctive role to play. I think that vision from scripture ought to help us think about the evolutionary process and how we do science.

How would you respond to someone who would say, ‘Oh here’s a biblical scholar who has spent too long in the library and has gone liberal!’

A student of mine who was an elder in a church introduced me at a retreat once, saying ‘Richard Middleton is more liberal than the liberals and more conservative than the conservatives’, and that was at a Presbyterian church! In some ways my theology doesn’t fit any category. You don’t need to try and be conservative or liberal, you need to be biblical and if that shatters certain preconceptions liberals have, or conservatives have, so be it. But people who know me will never think I’m liberal, actually. I’m trying to allow the Bible to shape our theology and not let the Bible always say what we thought it meant. My vocation for the church is to bring serious biblical analysis to bear, that we might re-shape our theology in a biblical direction.

Can we go specifically to how the Bible and evolutionary account come together?

I start with what the Bible says. We tend to think of the first humans as Adam and Eve, but Genesis 1 speaks of a population group called ’ādām – humanity – and Genesis 2 speaks of two people. One is called the human, and one is called the woman. The human becomes a name ’ādām (Adam), and the woman’s name becomes life (ḥavvâ). These tend to look like symbolic names, so I don’t ask the question ‘which creation account Genesis 1 and 2 is really more true?’ The Bible doesn’t answer the scientific question of evolution, it answers the question of the meaning of life. There is nothing that says we must think of the first humans as a pair that God created instantaneously.

What do you really hope people will take away from this kind of discussion about science and the Bible?

Pexels [Public Domain]

But the connection to the present reality is also important because if the Bible only remains in the distant past, it doesn’t speak to the church today. The two problems are that scholars tend to study the Bible as an abstraction, but many laypeople read it as if it’s obvious what it says and therefore miss some of its depth. My vocation is to be a scholar of scripture, taking what I learn and making it accessible to the church.

Thank you very much for helping us to do that today.

Born and raised in Jamaica, J. Richard Middleton did his B.Th. at the Jamaica Theological Seminary (Kingston). He holds an M.A. in philosophy from the University of Guelph (Canada) and a Ph.D. in theology from the Free University in Amsterdam (the Netherlands). He is Professor of Biblical Worldview and Exegesis at Northeastern Seminary (Rochester, NY), adjunct professor of Old Testament at the Caribbean Graduate School of Theology (Kingston, Jamaica) and is past president of the Canadian Evangelical Theological Association (2011-2014). Author of A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology (Baker Academic, 2014) and The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 (Brazos, 2005) has co-authored and edited other works and published articles on creation theology in the Old Testament, the problem of suffering, and the dynamics of human and divine power in biblical narratives. His books have been published in Korean, French, Indonesian, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Born and raised in Jamaica, J. Richard Middleton did his B.Th. at the Jamaica Theological Seminary (Kingston). He holds an M.A. in philosophy from the University of Guelph (Canada) and a Ph.D. in theology from the Free University in Amsterdam (the Netherlands). He is Professor of Biblical Worldview and Exegesis at Northeastern Seminary (Rochester, NY), adjunct professor of Old Testament at the Caribbean Graduate School of Theology (Kingston, Jamaica) and is past president of the Canadian Evangelical Theological Association (2011-2014). Author of A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology (Baker Academic, 2014) and The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 (Brazos, 2005) has co-authored and edited other works and published articles on creation theology in the Old Testament, the problem of suffering, and the dynamics of human and divine power in biblical narratives. His books have been published in Korean, French, Indonesian, Spanish, and Portuguese.