Every time you breathe, a series of air pockets with a combined surface area the size of a tennis court is bathed with oxygen. In your lungs, the boundary between air and blood is so thin that oxygen and carbon dioxide can diffuse freely from one to the other. So every time your heart beats, the blood rushing around your body is refreshed with enough new oxygen to keep you alive.

A while ago I commented on the lack of current science in Christian worship music, but the very next month a song was released that at least hinted that we know enough about the working of our bodies to show us something amazing about God.

You show your majesty

In every star that shines,

And every time we breathe .

Your glory, God revealed

From distant galaxies

To here beneath our skin.

excerpt from Magnificent (Kingsway, 2011)

Matt Redman, who co-wrote the song with Jonas Myrin, is an astronomy geek. With Pastor Louie Giglio he co-wrote the book Indescribable: Encountering the Glory of God in the Beauty of the Universe, which is a mixture of science, worship and beautiful pictures. Both authors ‘share an appreciation for the universe that surrounds us, particularly its unique ability to lift our hearts to see how massive and mysterious God truly is.’

The microscopic level on the other hand – what goes on ‘beneath our skin’ – is less available to ordinary people. You might enjoy the beauty of plants or animals, and the wonderful details you see when you look at them close up, but it’s not quite the same as astronomy. It’s difficult to feel the same sense of awe at a dandelion that you might experience looking up at the sky on a dark night.

As a biology geek, I have had the privilege of exploring the micro-world to my heart’s content. Studying living things at the highest-possible level of magnification does bring a sense of awe, and I want to share that with others. So after reading Redman and Myrin’s song lyrics I went to the Cambridge University Science Library to learn some more details about how my body works.[1]

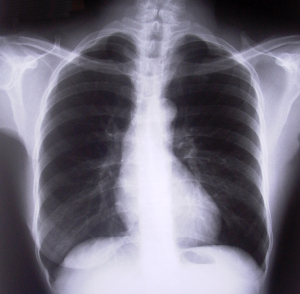

The air that’s drawn into our lungs when we breathe ends up in the alveoli: thousands of tiny sacs with a combined surface area of up to 100 square metres. These minute air pockets are covered with blood vessels, and it’s here that the exchange of gases happens.

When your heart is beating at a normal (resting) rate, a single red blood cell takes about three quarters of a second to travel through the small capillaries in your lungs. But in just a quarter of a second that cell has already received all the oxygen it needs from the air. So if your heart rate increases and the blood flows faster, you’re covered.

After reading these facts and figures, I couldn’t help sitting in my chair just breathing. I became aware of my heart beat, and tried to imagine the processes happening inside my body. Constant blood flow and gas exchange, breathe in, breathe out, keep it oxygenated. After consciously focusing on these things, it can take a while to become unconscious of them again. Thankfully we don’t have to concentrate on making our internal organs work together, but a complex network of signals and feedback loops keeps everything running smoothly.[2]

Redman and Myrin wrote in their song,

You are higher than we ever could imagine

And closer than our eyes could ever see.

For me, the universe demonstrates God’s awesome power. This is a place made by a being whose imagination is not limited by time and space. God is more than anything I could ever imagine. Biology, on the other hand, helps to remind me of his closeness.

I am a product of a long and painstaking process of continued development over aeons of time. Beneath my skin are the incredibly detailed, beautifully regulated processes that give me life. Jesus said that ‘even the very hairs of your head are all numbered.’ The knowledge that God made me and knows every detail of my physiology is both amazing and humbling.

[1] Cindy L. Stanfield, Principles of Human Physiology, 4th Edition (San Francisco: Pearson, 2011), 451-506.

[2] And when things go wrong it’s a humbling reminder how reliant we are on these ‘simple’ biological processes.