If all truth is God’s truth, then science must have an impact on our theology. This was the central message of theologian Steve Motyer’s seminar in the God in the Lab evening series at London School of Theology (LST) earlier this year.

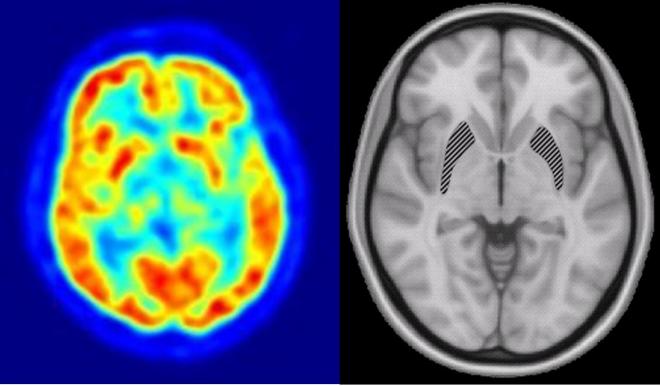

Having taught theology and counselling for a number of years as part of his role at LST, Motyer is all too aware of the connection between mind and brain. Neuroscience is showing that everything we call ‘mind’, including feelings, instincts and intuitions and spiritual apprehensions, is rooted in brain function. Various parts of the brain are active when we pray or have spiritual experiences. If those parts are damaged, then we can lose the capacity for certain spiritual activities and feelings. So the spiritual and the physical are not separate, but intersect completely with each other.

Motyer then used evolutionary biology as an example to show how science can inform theology in four main ways. The evidence for an evolutionary account of earth history and of human origins is overwhelming.* So first of all, when we say to God that “all creation worships you”, the creation we can now have in mind is a grand and glorious place, extending vastly in time as well as in space, and this enlarges our view of God.

Accepting evolutionary biology can also lead to a greater emphasis on the mystery of God: on what we don’t know as well as what we do. Suddenly verse 33 of Romans 11, ‘Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God’, takes on a bigger meaning. God’s riches include his amazing creatorial freedom and resources in every department. We can see his wisdom in the management of his world, and God’s knowledge includes his understanding and inventive capacity.

Another impact of evolutionary biology on theology is to reinforce the biblical view of time, which can also enlarge our view of God. For example, Psalm 90 speaks of God existing before ‘the mountains were brought forth’, and reminds us of his perspective: ‘For a thousand years in your sight are but as yesterday when it is past, or as a watch in the night’.

Finally, evolution brings an enlarged theology of sin and death. There was no concern about either of these when the dinosaurs roamed the earth – they could kill each other without it being a problem. Wrongdoing only became an issue when creatures became self-conscious, which was probably at some point in the last 70,000 years. Reflecting on themselves and their relationships with each other, they finally realised that it doesn’t do to kill or steal from each other. Similarly, death was not a problem until we could reflect on our existence and life-span, and give some value to ourselves and others, and begin to hate the loss that death entails.

How then, does this more biological view of sin and death fit with the Bible? Salvation is written into the story of creation right from the beginning, by a God who brings to birth self-conscious beings who can love themselves, others, and himself. God then shows his love for the people he has made by becoming one of them.

So according to Motyer, biology is a huge boost to faith and worship because it paints a bigger, richer picture of the world. I was fascinated by his lecture because it is an example of how science can have a very positive impact on theology. For Christians, whether or not you accept this interpretation, I hope you can agree that it is good to expand our view of God by expanding our view of the world he created. I’m sure there will be more to come from theologians and biblical scholars as they interact with science in the coming years, and I hope it will be a very fruitful conversation.

* Here, Motyer recommended Denis R. Alexander, Creation or Evolution: Do We Have to Choose? (Lion)