How does theology contribute to science? This is a question that developmental biologist Jeff Hardin has answered many times. I met Jeff several years ago when I first interviewed him for the God in the lab book, and was immediately intrigued to learn that he has studied both of these subjects. In today’s guest posts, he explains his own perspective on science and theology.

As Americans go, I’m a bit of an odd duck. Before my PhD in Biophysics at the University of California-Berkeley, I received a Master of Divinity degree, focusing on theology and philosophy. For me, it is important that theology and science fit together, not just as an intellectual exercise, but at a deeply personal level.

I am often asked –by well-meaning friends of faith and curious colleagues alike – about the value my theological training has been to me as a Christian in science. This question is a curiously modern one compared with the much more time-honored idea that the study of nature should enhance the study of God and vice versa.

Take this surprising source: the frontispiece to Darwin’s The Origin of Species, where Francis Bacon says, “let no man…think or maintain, that a man can search too far or be too well studied in the book of God’s word, or in the book of God’s works.” This “Two Books” language is not exactly original to Bacon. The first two verses of Psalm 19 say this:

The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands. Day after day they pour forth speech; night after night they display knowledge. [NIV]

The Psalmist luxuriates in the creation; the regularities of the heavenly bodies provide unspoken testimony to God’s awesome power and faithfulness, declaring God’s glory, His gravitas. “Pour forth” in the original implies the idea of a bubbling brook: the creation is irrepressible in praise of its Creator.

As moderns, it is easy for us to miss the import of these lines, but they provide a key Leitmotif for doing science. The creation is objective and intelligible; it is not impelled by capricious deities, so its regularities can be studied. Moreover, it has contingent independence.

For the Psalmist, the world is like a work of art. As such, it can – and indeed begs – to be studied on its own terms. And that means that scientists are called to as much excellence and integrity as we can muster as we ponder the complex yet elegant mathematical language of unifying equations, the dizzying complexity of a developing embryo, or the staggering diversity of ecosystems. Getting the details wrong about any work of art would be an affront to the artist who created it.

So science can enhance faith and worship. But how does faith enrich science? Psalm 19 shows wonderful reciprocity:

The precepts of the LORD are right, giving joy to the heart. The commands of the LORD are radiant, giving light to the eyes. The fear of the LORD is pure, enduring forever.

God has provided us a wonderfully complementary, two-volume work. If Volume 1 is the “book” of God’s world, then the companion volume is the book of God’s Word.

This second volume provides a key ingredient we scientists often lack: perspective. As Alister McGrath puts it, Christian faith has an “explanatory capaciousness” that enriches science and the scientist. And as C.S. Lewis so famously put it, “I believe in Christianity as I believe the sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it, I see everything else.” The joyful exhilaration of discovery, the epistemic virtues of truth-telling and truth-seeking, and the ethical impetus for the right applications of technology all find a home in this larger context. For the Christian who is a scientist, here is a marvelous opportunity to glimpse the whole of God’s story.

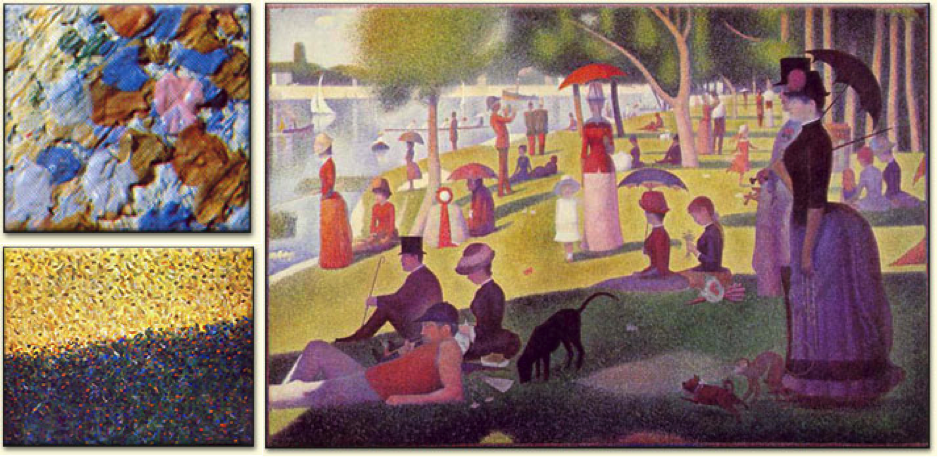

Perhaps an illustration is in order. I live a few hours from Chicago. In its Art Institute hangs a massive painting by Georges Seurat, called Sunday Afternoon on the Island of Le Grand Jatte. This monument to pointillism can be studied at the minutest of levels to appreciate the application of pigments, and the theory of color that underlies them. Such a close-up view is a metaphor for the daily work of science, with its attention to reductionist details of some natural process.

Rarely do we scientists step back far enough from our work to realize that, like Seurat’s dabs of color, our corners of the universe are part of a larger scene. In the end, of course, the sweeping scene of Parisian life Seurat depicts can only be fully appreciated by stepping far away from the massive canvas. In the same way, Volume 2 of God’s masterwork gives us perspective on life’s meaning. We gain even more, of course. We learn unique things about Seurat from intensive study of his work. But we learn of the intentions and desires of Seurat the person more directly through his verbal communication. In much the same way, we learn about God’s creativity through His world, but about His intentions and desires by reading His Word, and especially His Living Word (John 1:14).

The world and the Word together are meant to lead us to a common author. Making coherent connections between these two books is not always easy. But it is definitely worth the effort.