Sound wave by betmari. Flickr. (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Music, whispers, phone calls, the alarm clock, the cry of a baby – the ear mediates our auditory interactions with the world. The things we hear may make us laugh or cry, enhance a film or make a subtle point without words, cheer us up or soothe an angry mood. The interpretation of sound and what it means to us is the responsibility of the brain, but the pathway that takes a pressure wave in the air to the point at which the brain receives the signals that represent that wave is complex and fascinating.

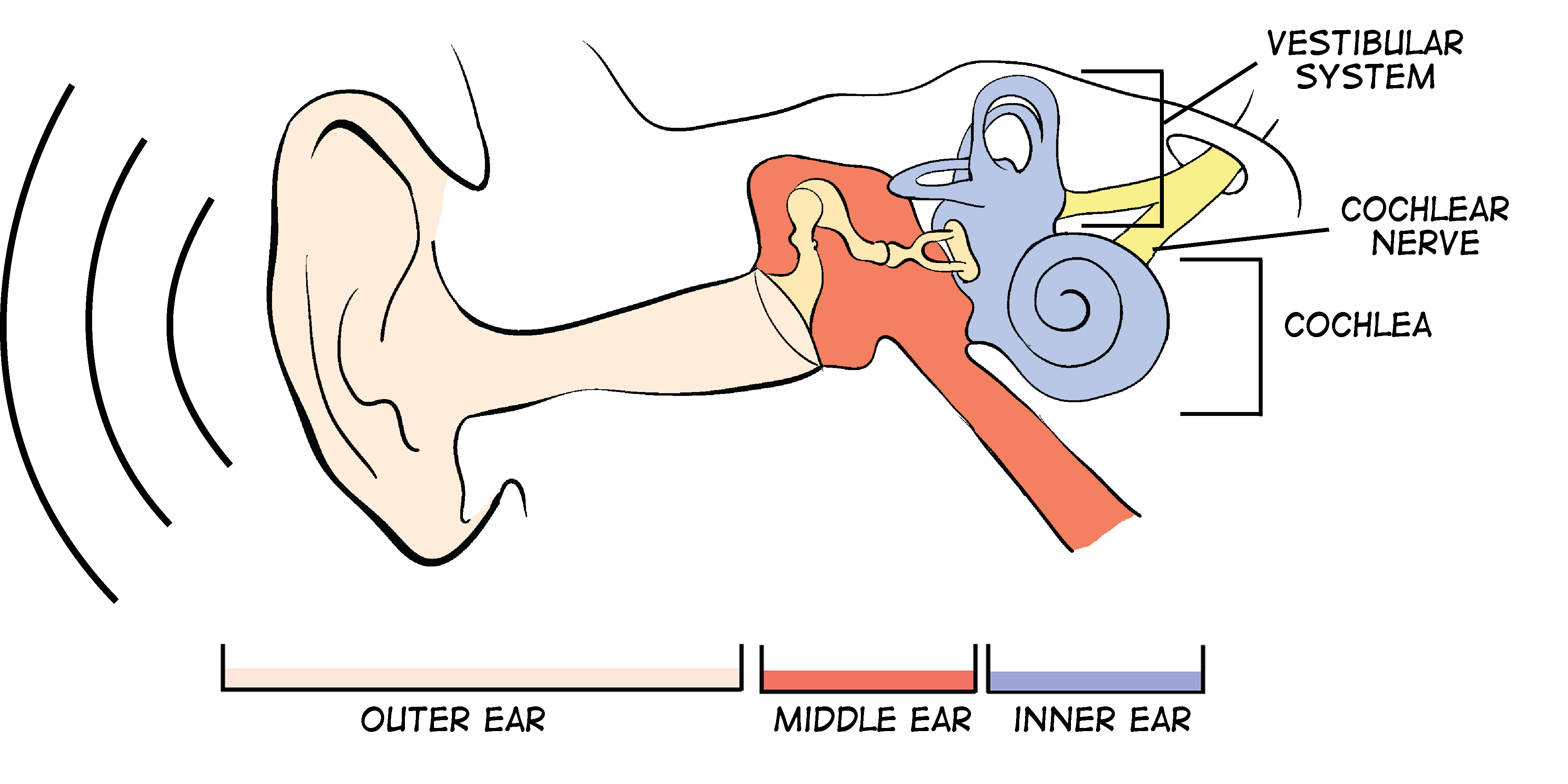

© Morag Lewis

The ear is made up of three parts: outer, middle and inner. The outer part – the bit that sticks out from the head – funnels sound through the ear canal to the middle ear, where the tiniest bones in the body amplify and transmit sound waves to the inner ear. Inside the inner ear is the vestibular system, which allows us to sense gravity and motion, and the spiral seashell shape of the cochlea, which holds the organ of Corti, which is responsible for our hearing.

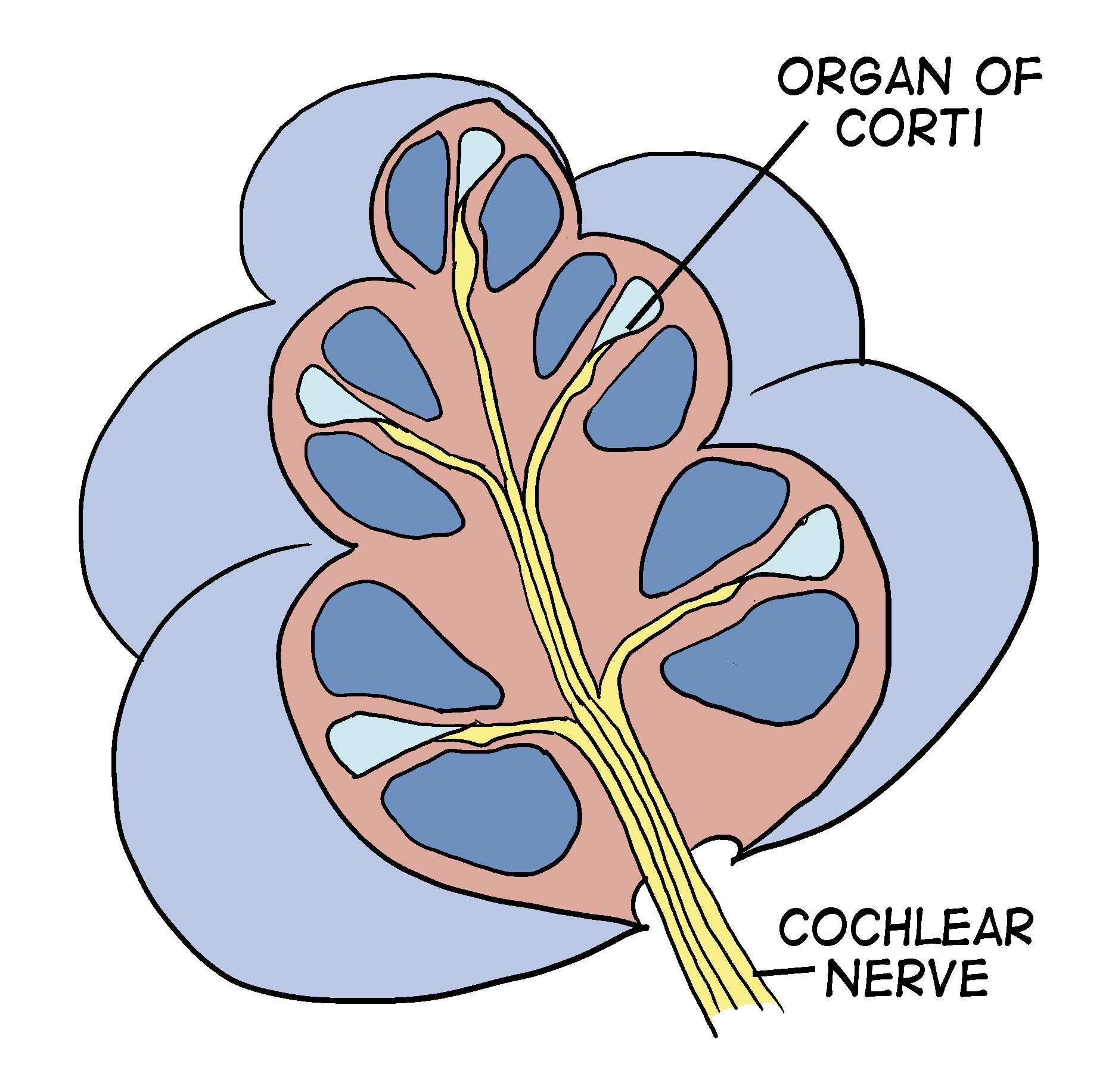

© Morag Lewis

The sensory cells which line up along the organ of Corti are called “hair cells”, because they have protrusions on top which look like a bundle of hairs. These bundles are the machinery of hearing. As the sound waves vibrate through the organ of Corti, the “hairs” move and tiny mechanical channels open, allowing ions into the hair cells to generate the signal which then passes along the nerve to the brain. The malfunction of any part of this pathway from outer to inner ear can result in deafness.

Hearing loss is often seen as a natural part of ageing. By the age of 70, more than half the population have lost enough of their hearing that they would benefit from a hearing aid. And yet, some people maintain good hearing throughout their lives. We know that many things affect hearing throughout life, such as noise exposure (rock concerts or explosions) and drugs, but we also know that a large contributor to hearing loss is genetics.

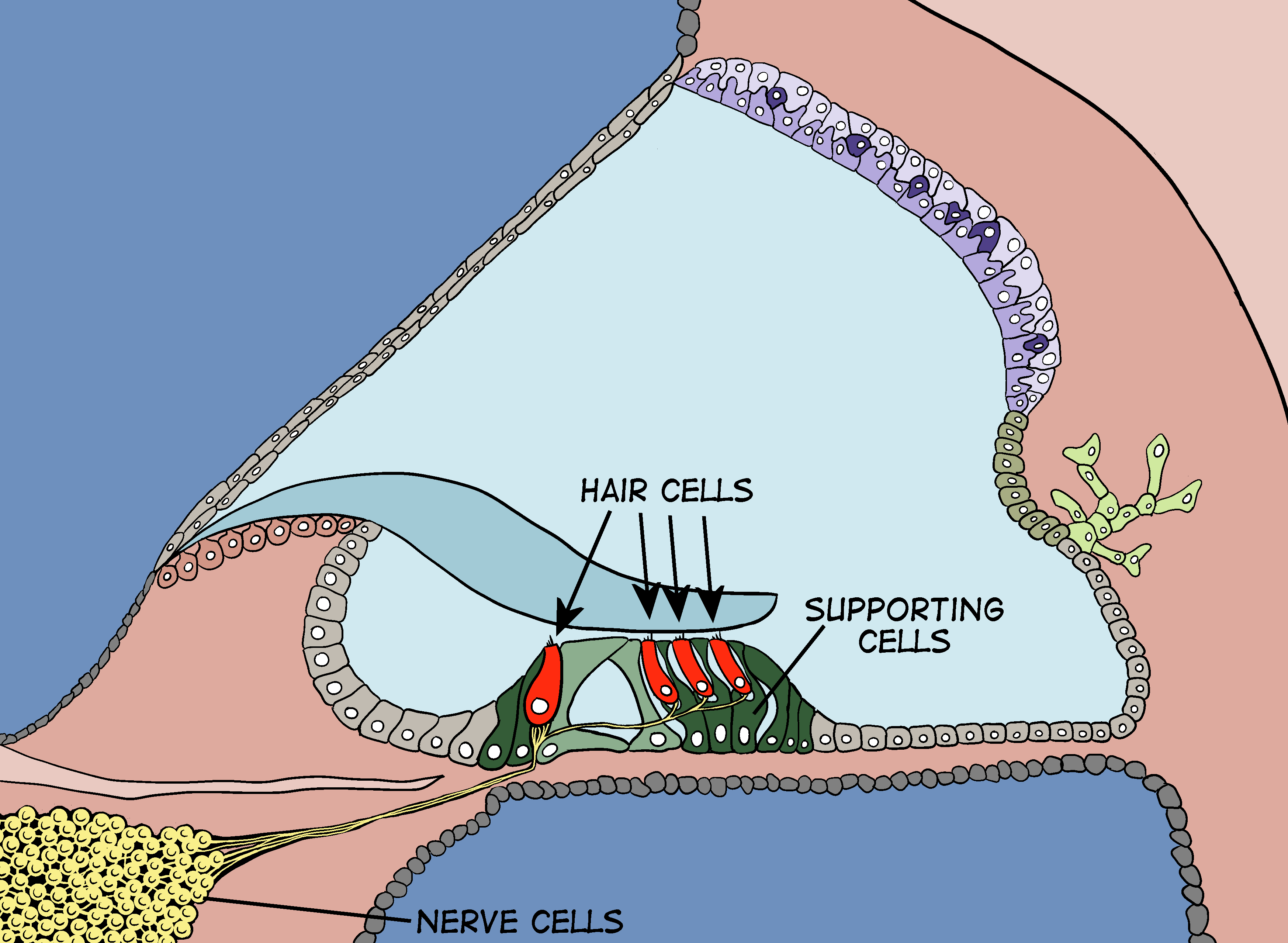

© Morag Lewis

There are only about 15,000 hair cells in a human ear, compared to the eye’s 130 million photoreceptors. They are capable of sensing an enormous dynamic range. They are precisely arranged along the organ of Corti with a specific orientation. They have to last a lifetime, because in mammals hair cells do not regrow. They are supported by a wide array of other cell types, without which they will die.

The genetics involved in setting up and maintaining the structure of the organ of Corti is complicated and, as yet, mostly unknown. One of my favourite aspects of my job is discovering new genes involved in hearing loss – because each one is a potential target for treatment, but also because each one is a piece of an enormous jigsaw puzzle. I feel very privileged to be discovering things about this intricate and beautiful little bit of God’s creation.

I didn’t intend to study human disease. In fact, when I went to university I was torn between particle physics and molecular genetics, and if I had had to make a choice I would probably have chosen physics. Two weeks into a course which allowed me to try both for a bit longer, I realised physics wasn’t for me! I spent most of my undergraduate years on geology, and after I graduated studied computer science for a year before coming back to biology for a PhD. Even that had nothing to do with the ear – I spent four years studying the comparative evolution of the bristles on the back of the malaria mosquito.

Ten years later, I am very grateful for the chance to work on the genetics of hearing loss. The ear is complex, delicate and fascinating. Its molecular machinery is unique, and so much of the genetics behind it remains to be discovered. It is incredibly rewarding to be working on something which could make such a profound difference to so many people. I hope and pray that the work I contribute to will lead to treatments for hearing loss.

Dr Morag Lewis is a Research Fellow at King’s College, London, where she studies the genetics of deafness, focussing on progressive hearing loss and the regulatory networks of genes which set up and maintain the hair cells. Based in Cambridge since she was a student, Morag divides her spare time between reading, playing board games and making comics (you can find her work on http://www.toothycat.net). She is a member of Eden Baptist church.

Dr Morag Lewis is a Research Fellow at King’s College, London, where she studies the genetics of deafness, focussing on progressive hearing loss and the regulatory networks of genes which set up and maintain the hair cells. Based in Cambridge since she was a student, Morag divides her spare time between reading, playing board games and making comics (you can find her work on http://www.toothycat.net). She is a member of Eden Baptist church.