© K Hardy, Wellcome Images, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Ruth Bancewicz writes: One of the hardest things to do as a Christian is to work alongside others whose faith we share, but who have different views on issues that are close to our hearts. Almost as soon as I started working for Christians in Science just over 15 years ago I began to encounter a range of opinions. Whether it was creation or evolution, the status of the early embryo, or the existence of a soul, I encountered people who followed Jesus and held the Bible in equally high regard, yet had different views to each other on some of these very key issues.

The most important part of this formative time was the way in which I saw people interact with each other with grace and understanding. These issues are very difficult to fathom and, where modern medical advances are concerned, the Bible usually has nothing specific to say about them. We are left to apply general principles and do our best to fulfil our various callings in life. Caroline Berry was one of these people. As an evangelical Christian who holds a more ‘liberal’ position than the majority, she was sometimes in a difficult position, but she is gentle with her views and generous towards those she disagrees with. Her story is both thought-provoking and challenging, and I’m delighted that she has shared it here.

Caroline Berry writes: My early life was fairly traditional (apart from being born in Baghdad): a church going family, boarding school as my father often worked overseas, and deciding Jesus should be Lord after being taken to hear Billy Graham at Wembley. Then medical school in London where I joined a lively church. Here I met Sam Berry, starting his PhD at UCL and we got married at the halfway stage of my course. After full qualification a research post seemed a good way forward but then we had twins, followed by one more baby, and medicine had to take a back seat.

After a few years of fulltime motherhood Sam thought I needed to do something more stimulating and suggested I applied the skeletal variants he was using to trace population movements in mice as a potential tool for studying population movements in humans. So I registered for a PhD in the genetics department at UCL and we had interesting holidays or visits to museums in several Scandinavian countries and various parts of the British Isles. After five years all was completed, the spelling of cemetery in the thesis corrected, and the PhD awarded. Sam was away so the celebration was ice cream for tea with the children!

Medicine was, however, moving. Genetics was becoming recognized, chromosome disorders such a Downs and Turners syndrome were being identified and DNA manipulation showed huge future potential. Pre natal testing was becoming possible and there were no medics with any knowledge of genetics as nothing of practical use was taught in medical school.

At Guys Hospital Prof. Paul Polani had the most up and coming genetics research and clinical unit, and he needed a clinician. He agreed to give me a trial year to see how it went. I was a bit hesitant as pre-natal testing could lead to abortion if a serious abnormality, such as spina bifida, was found. It seemed right to go forward on the understanding that if I found this to be incompatible with my Christian walk I would step aside. However, it took only a few weeks of meeting people facing such difficult problems and decisions that it was clear there is a real need for Christian clinicians in this branch of medicine.

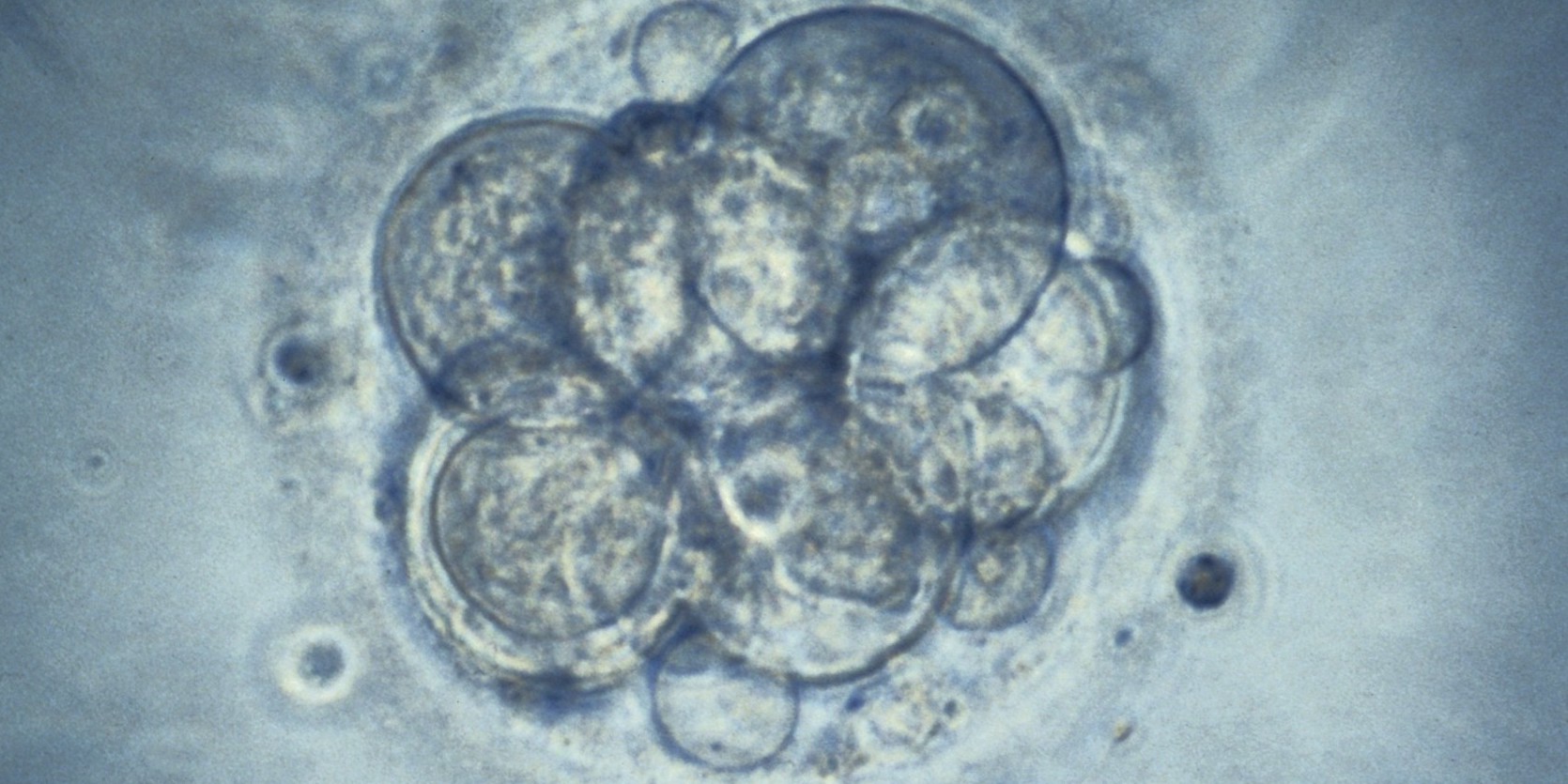

So the work and the department grew as medical genetics expanded. But all the time new ethical dilemmas appeared. The possibility of IVF caused much dissension among Christians. Was this meddling with Gods creation? Should babies be ‘begotten’ or ‘made’? The birth of the healthy Louise Brown in 1978 was a landmark but gave rise to further issues: what is the status of the very early embryo? Is it a person for whom Christ died or is it a cluster of cells in a petri dish on which research could be permitted? Christians were strongly divided. I needed at least to try to have a God-shaped opinion. Reading the Bible from cover to cover to find inspiration I had to conclude that God is a God of compassion who is concerned for the weak and the marginalized. There are times when priorities have to be decided as there were often conflicting needs. Should people struggling in the world have priority over the cells in the petri dish? Care for the vulnerable was double edged. Who had priority, the very disabled but unborn fetus or the potential parents perhaps already struggling with a severely disabled child?

There seemed to be times when Christians are called to differing positions. John Wyatt, a neonatologist, and I differ but I respect his calling to put the fetus first whereas my priority might be the parents.

In the early days differences between Christians were quite strident. The Christian Medical Fellowship arranged a weekend away for Christian medics and theologians with differing views to meet and talk face to face.

I have one powerful memory of that weekend. I was leading a seminar on the ethics of sperm donation. Those present seemed to be mostly middle aged men who strongly disapproved of my suggestions that there were occasions when it could provide an acceptable answer for a couple having to cope with a serious genetic disorder. Was this adultery or might it be a way forward? We were near Biggin Hill and it was September when the Battle of Britain is celebrated. Out of the window there appeared, flying low and menacingly, a Lancaster bomber. My reaction was ‘how horrible, a machine wreaking death and destruction on innocent people’ The others in the group all ran to the window, excited and enthused at the sight of their boyhood hero. I realized that our ethical views are easily coloured by our life experience, to them the Lancaster bomber was a liberator from Nazi domination, not a weapon of destruction. Although being aware of ‘the slippery slope’, we need to put ourselves in others’ shoes.

Being a clinical geneticist in those formative years was exciting if stressful. It seemed right as a Christian to be prepared to take the risk of being wrong rather than being too obsessive about having clean hands. In 1987 the various conclusions I reached were published in The Rites Of Life (Hodder & Stoughton). Since then, progress in molecular genetics has softened some of the dilemmas but new ones arise. Genetics is now all-pervasive but there is still a serious need for Christians to be involved, contributing to both the ethical and the scientific discussions.

© C Berry

Caroline Berry is a retired Consultant Clinical Geneticist who worked at Guy’s Hospital in London. She was secretary and then a trustee of Christians in Science for fifteen years. She is a long term member of the Christian Medical Fellowship and at one time chaired its Medical Study Group. She has three adult children and has been an active member of her local church for 55 years.