Nearly 150 years ago, two men who pretty much no one has now heard of set out to convince both the general and the highly educated public of a falsehood—and pulled it off. They have fooled the minority, and the majority. They have fooled a lot of the experts. Their alternative version of history— one which is quite easy to show is untrue—remains the most common view to this day. Somehow, against all of the odds, they have successfully fooled the world.

So, who were they? What did they say? And how, exactly, did they get away with it?

John William Draper (1811-1882) was considered one of the greatest living scientists in a legendary era of science, but he had also become an acclaimed historian, philosopher, and best-selling author to boot. Whenever Draper spoke—no matter the topic—the world, in awe of him, listened.

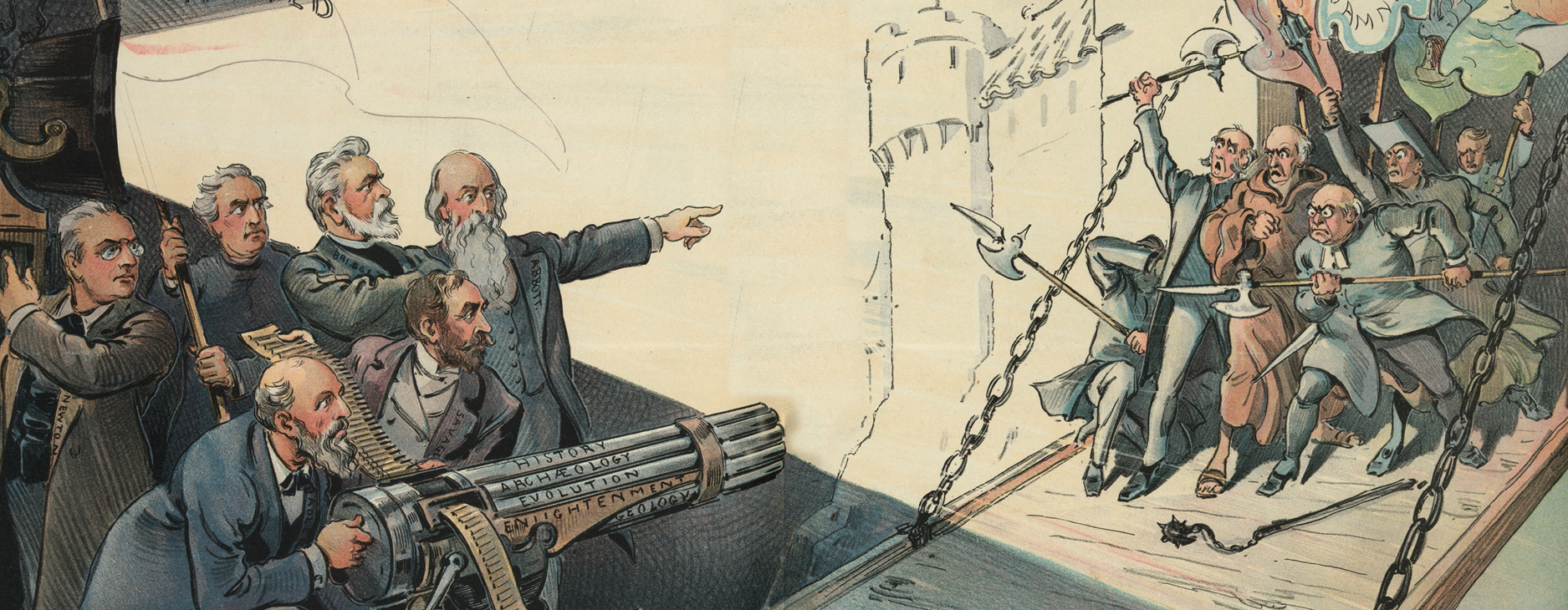

Buoyed by his various successes, Draper now turned his mind to an entirely new topic altogether. What, he wondered, was the real relationship between religious faith and scientific knowledge? Unafraid of controversy, and believing himself to be best placed to comment, Draper decided to write what he hoped would soon be the go-to text on the matter. The title of his study betrayed its conclusion: A History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science.

Conflict is uncompromising in its critique of organized religion, and gushing in its praise of freethinking science. Despite his popularity, Draper’s final conclusion was still a controversial one. Perhaps, on its own, Conflict might not have been quite enough to settle the matter. The thing is, though, it wasn’t on its own—not for long.

Andrew Dickson White (1832–1918) studied history and English literature at Yale. He won a number of prizes for his essays and public speaking, including one valued at $100—the highest award available at any university in the world at the time. After graduating, he took up a professorship in history and English literature in Michigan. Then, in the 1860s, White’s rich lecturing career was brutally interrupted by the American Civil War. He was promptly nominated for and elected to the New York State Senate.

White’s new fellow senator, Ezra Cornell was seriously rich—but, as a committed Quaker, he wanted to do something worthwhile. White, of course, was ready with a suggestion: together, the two of them should found an innovative, modern university where religion and dogma would not hold back study. White’s enterprising brainchild faced stern opposition from the off. The university did indeed open in New York in 1868—and it took in the biggest entering class of any American school in history.

White’s anger, however, continued to simmer. For him, the vociferous attacks on his plans had confirmed what he had suspected for quite some time—that dogmatic religion was only ever a dreadful thing. And perhaps, he thought, it was time to fight back. In 1896, his vast survey of history, philosophy, physics, theology, biblical criticism, biology, sociology, and more was pulled together into one totemic volume—a lengthy, exhaustive, and ruthless attack on dogmatic religiosity everywhere. He called it A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom.

That Conflict and Warfare appeared in the same era, had the same broad scope, and agreed on so much added a great deal of weight to their claims. Even their dissimilarities were beneficial—they appealed to different readers, and so their combined message spread both far and wide. Such was the combined influence of Conflict and Warfare that they sat on bestseller lists for decades, sold all across the globe, were translated into all sorts of languages, and became the twin final words on their topic.

And yet, in their desperation to dismiss dogma, our two authors managed to fall foul of their own accusations—for, during their two projects, they uncritically accepted, wholeheartedly believed, and then wilfully propagated an entire collection of myths of their own. Between them, then, John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White did more than launch a small-scale conspiracy theory, or gather a handful of limited but loyal followers for a couple of years. Instead, they fooled the world.

The series of myths that Draper and White spread about science and religion are known today in the literature as the conflict thesis. Thanks to the dedicated and committed research of a band of specialists operating since the 1980s at least, the conflict thesis has now been thoroughly debunked. One by one, the tales spun out in Conflict and Warfare have been shown by historians to be either entirely false, horribly misunderstood, or deliberately misrepresented. Yet no one, it seems, is actually listening to them.

Over the last century and a half, despite its untruth, the God-or-science mantra has become firmly embedded in our culture. Indeed, Draper’s forceful summation of it—his “cannot have both” formulation—can be found almost everywhere. A 2013 survey of high school students in the United Kingdom, for instance, found that the majority agreed with the statement “the scientific view is that God does not exist.”

Conflict and Warfare, it would seem, have become dangerously self- fulfilling prophecies—it can get quite horrible out there at times. Which, by the way, is the last thing that Draper and White would ever have wanted.

Draper himself was no atheist; neither was White. They were not even agnostic. In fact, both thought of themselves as followers of Christ, and viewed their books as significant contributions to his cause. They were writing, the two of them said, not to push science and religion ever further apart, but instead to bring them both back together.

We are left, then, with quite a few questions. If these two men intended to reconcile God and science, then how did they manage to make such a big mess of it? If they were so famous and successful at the time, then why has hardly anyone today even heard of Draper, or White, or their two books? Why does the conflict thesis hold such a strong grip now, more than a century after Conflict and Warfare were written?

This article is a series of extracts from chapter 1 in Of Popes and Unicorns: Science, Christianity, and How the Conflict Thesis Fooled the World by David Hutchings and James C. Ungureanu. Copyright ©2021 by David Hutchings and James C. Ungureanu and published by Oxford University Press. 280 pages. All rights reserved.