© Varglesnarg, Freeimages.com

But [Peter] replied, “Lord, I am ready to go with you to prison and to death.” Jesus answered, “I tell you, Peter, before the rooster crows today, you will deny three times that you know me.” Luke 22:33–4

The Lord turned and looked straight at Peter. Then Peter remembered the word the Lord had spoken to him: “Before the rooster crows today, you will disown me three times.” And he went outside and wept bitterly. Luke 22:61–62

When they had finished eating, Jesus said to Simon Peter, “Simon son of John, do you truly love me more than these?” “Yes, Lord,” he said, “you know that I love you.” Jesus said, ‘Feed my lambs.’ John 21:15

Every scientist understands the meaning of error—though perhaps not that of forgiveness. As Alexander Pope put it: “To err is human, to forgive divine.” Occasionally, the chemist’s experiment may go all the way to the finish before an error is discovered. Then—consternation. That white powder in the final product bottle is not, after all, the correct product that the chemist thought he or she had made! Why not? We must know why. Every scientist will check and re-check every part of a failed experiment. Usually they will find the cause of the problem. Just occasionally (but far more often than they will care to admit), they will find that the problem is themselves! They have made a mistake. Can science forgive them? Can they forgive themselves?

An error is generally the last thing we have to (or wish to) take into account. But we all make them—and must plan to avoid them. For errors—casual ones, hasty ones, hapless ones and even frankly inexplicable ones—can on occasion lead to accidents. In any case they will waste time and materials, whether they were errors of planning the chemistry, handling the chemicals, operating the equipment or, as happened to me on a few occasions, plain incompetence in remembering what to do and when!

The most embarrassing are simple practical errors, ones so simple that a child would have spotted them. A classic one, of which I have been guilty of several times, comes while the chemist is collecting the liquid dripping from the bottom of a chromatography column. The liquid is collected in empty test-tubes and usually this is done using an automated fraction collectorthat moves racks of empty tubes around—as long as the chemist has put them in place! But if the chemist forgets to add more tubes, then after the last full tube has been moved away the column will simply be dripping the precious product solution away to waste! When the chemist notices, he leaps to turn off the column, then kicks himself around the lab—while being grateful, nonetheless, that only his pride and performance have been injured, not anything worse…

Safety statistics are said to show that the most accidents are suffered by laboratory chemists in the first two and the last five years of their careers—before they are fully trained or when they have begun to get “demob happy”, as the post-war saying goes. Accidents are also much more of a danger for scientists who only work occasionally in the laboratory than to those who are there every day, for lack of practice is a hazard in itself. Yet they also happen to experienced, steadily working chemists too! For we all know that “Familiarity breeds contempt”, as the moral of one of Aesop’s fables puts it. And even when all these are allowed for, there is still a significant level of mistakes (and a thankfully very much smaller one of accidents) that continues through all of laboratory life.

For even the wisest scientists are frail and fallible. We all wince with Peter as he sees Jesus looking at him. Yet we all know that few of us would have got as far as Peter did with Jesus, and none could assume they would not crumble as he did. Therefore the reinstatement of Peter to Jesus’ love after the Resurrection comes as a relief to all of us, too. I have stood at Tabhga on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, at the spot where Jesus forgave Peter. It is a shore of hard rock and black basalt pebbles, with nothing soft about it. But then, Jesus’ love and forgiveness were not soft, either…

As the late Major Ian Thomas, founder of Capernwray Bible School, used to put it, “What does God expect of you? Nothing but failure.” We can in any case give nothing to God. How could we do anything for the God who made the universe? In the Psalms, He reminds us that it is pointless to try, “for every animal of the forest is mine, and the cattle on a thousand hills. I know every bird in the mountains, and the insects in the field are mine. If I were hungry I would not tell you, for the world is mine, and all that is in it” (Ps. 50:10–12). Because of this, those who have become followers of Jesus Christ are not condemned by their humanity, but set free by it…Error does not destroy us if we learn from it. We need to take this truth to our hearts. We must do that now.

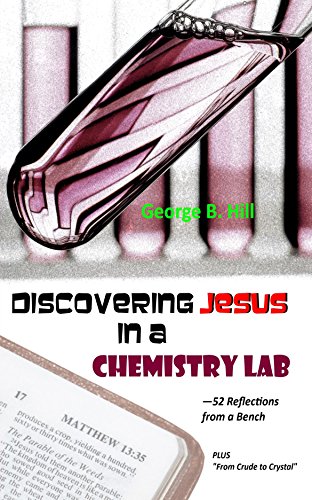

This post is a series of extracts from chapter 47 in Discovering Jesus in a Chemistry Lab – 52 Reflections from a Bench by George B. Hill (Lulu, 2017), 372 pages, £14.99. Reproduced here with permission of the author, who blogs at hillintheway.

This post is a series of extracts from chapter 47 in Discovering Jesus in a Chemistry Lab – 52 Reflections from a Bench by George B. Hill (Lulu, 2017), 372 pages, £14.99. Reproduced here with permission of the author, who blogs at hillintheway.