© Luis Paredes, Freeimages.com

The world seems to be full of disasters, appearing on our TV screens and newspapers on a weekly basis. Some are clearly caused by humans: bridges fall down; buildings catch fire and incinerate many people; dams collapse and drown folk; terrorism and war inflict terrible suffering and atrocities. Others seem to be arbitrary, just “acts of God”: earthquakes; volcanic eruptions; floods; outbreaks of highly infectious diseases. They are things that we feel should not happen in a well-ordered world. Yet they persist.

From a Christian perspective, the problem is especially pointed. Christians believe in an all-powerful, sovereign God, who is perfectly just and completely loving: so why does he permit disasters to happen? … The message of this chapter is that what we call “natural” disasters − the floods, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes − are the processes that make this world a fertile, habitable place where humans can thrive. These generally beneficial natural processes are frequently turned into disasters, primarily by the actions, or inactions, of humans. Thus, we might term them “unnatural disasters” rather than “natural disasters”.

In the case of earthquakes, this is captured well by the aphorism “first the earthquake, then the disaster”. It has been applied many times, possibly starting with a 1970 earthquake in Peru which killed over 70,000 people. The disaster in Peru to which locals referred was the way in which subsequent heavily funded reconstruction and development programmes were directed from outside the affected communities by remote and aloof managers, with minimal regard for local leadership, organization, or community participation. In effect, they destroyed what had formerly been vibrant, self-driven, and motivated local networks and communities…

A major factor, which makes disasters more devastating today than in the past, in terms of the numbers of people killed or affected, is the exponential increase in global population: there are almost five times as many people alive today as there were a century ago. Add to this the fact that more people now live in cities than in dispersed rural areas and that those cities are usually in river valleys or by the coast, and it is inevitable that large numbers of densely packed people are far more vulnerable to natural hazards than in the past.

Another critical factor is poverty: high-income nations and rich people can generally buy themselves out of trouble, either by building safe homes before a flood or earthquake, or by rebuilding afterwards. Poverty makes that much more difficult, though not impossible. In terms of losses, the lowest-income countries bear the greatest relative costs of disasters. Human fatalities and asset losses relative to gross domestic product are higher in the countries with the least capacity to prepare, finance, and respond to disasters.

Set against that vulnerability caused by population increase is an equally rapid increase in scientific understanding of how the natural world works. In principle, this means that natural hazards can be recognized and understood better, and as a result appropriate mitigation or adaptation strategies put in place…

The most common disaster, which kills by far the most people, is flooding.… Floods disproportionately affect low-income countries and poor people, because high-income countries can protect themselves more effectively. Following tidal surges in 1953 which inundated large areas of eastern England and the Netherlands, killing 2,190 people, both the British and the Dutch built sea defences. The Thames Barrier and the Eastern Scheldt surge barrier are the largest moveable flood barriers on Earth, costing billions to build. But 30 million people living within one metre of sea level in the deltaic region of Bangladesh simply don’t have the financial resources to build such barriers, even if it were technically feasible in a delta. There is a clear moral issue here: present rising sea levels and increasing intensity of storms are caused mainly by global climate change resulting from the burning of fossil fuels in high-income countries. But people in high-income countries are not usually the ones who suffer the worst consequences – the people most affected played little part in causing the problem in the first place, and have least resources to cope with it.

Some Christian authors suggest that physical processes on Earth changed in a major way after humans rebelled against God in the Garden of Eden, writing that “earthquakes, volcanoes, floods and hurricanes were unknown before sin entered the world”. But geological observations show that there have been floods and tsunamis, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions since long before humans were present. Indeed, as already discussed, the very richness and fertility of this world which make it possible for humans to live and thrive is dependent on those same natural processes…

What went wrong, the Bible maintains, was that humans were not content to rule the world on behalf of God, as the first chapter of Genesis mandated. Instead, they wanted to be gods themselves, putting themselves in the place of God. They wanted to rule the world, whether their tiny patch, or with bigger ambitions, for their own selfish ends. The irony is that Adam and Eve already had everything possible for fulfilled lives, living in harmony with both God and the rest of creation. Certainly, there was work to be done: they had to till the ground and take care of it (Genesis 2:15). Life was never intended to be one of hedonistic indulgence and idleness. Rather, God had entrusted care of the Earth to humans, who were made in his image. They exchanged all that for a lie. All the relationships between God, humankind, and the non-human creation were affected. Humans lost their immediate access to God, and the rightness and orderliness of life in the Garden of Eden. Their relationships with other people were spoiled, soon resulting in murder (Genesis 4:8) and fear of others, and spoiling the relationship between men and women (Genesis 3:16). That selfishness in the way humans often use creation for their own purposes is the root cause of why natural processes often turn into disasters.

The way we ought to rule over creation was modelled by Jesus when he was on Earth. Jesus rules as a pastor–king; as a shepherd who is in charge of and cares for his flock; a rule that is devoted to the good of others and the glorification of God the Father rather than serving his own ends. For humankind, this rule pre-echoes the new creation, where redeemed people will reign with Christ (2 Timothy 2:12; Revelation 5:9–10; 22:5). That is also why, although all of creation is presently “groaning as if in the pains of childbirth” (Romans 8:22, NIV), it is waiting “with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God”, when it will be “set free from its bondage to decay” (Romans 8:19, 21)…

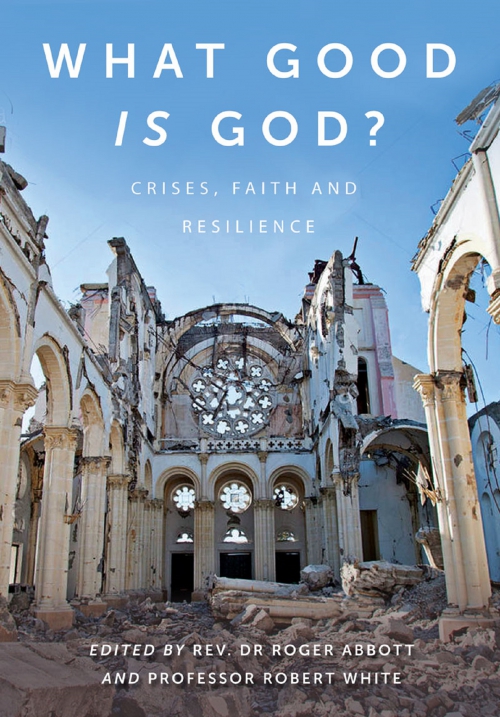

This post is a series of extracts from Robert White, ‘Disasters: Natural or Unnatural?’, in What Good is God? Crises, Faith and Resilience, Eds. Roger Abbott & Robert White (Monarch, 2020), 208 pages, £9.99. Reproduced here with permission of the author and publisher. Available for a discount at the Faraday online shop.

This post is a series of extracts from Robert White, ‘Disasters: Natural or Unnatural?’, in What Good is God? Crises, Faith and Resilience, Eds. Roger Abbott & Robert White (Monarch, 2020), 208 pages, £9.99. Reproduced here with permission of the author and publisher. Available for a discount at the Faraday online shop.